March 4, 2022

Howard

This report covers a thorough marketing analysis of the greatest show on Earth, Glastonbury!

Overview

This report provides insight into the marketing strategy of the Glastonbury festival and indicates the future marketing strategy and direction of the festival. The report does this by thoroughly understanding the company’s history, providing an in-depth analysis of the market (including a consumer profile), understanding the macro environment of the festival industry and evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the business, and finally analysing the currently used marketing communication methods. The report concludes that the Glastonbury festival should continue with its current successful marketing communications strategy into the future and suggests that by not having a profit-orientated strategy, the festival will maintain its uniqueness and exclusive appeal.

The Glastonbury Festival

The Glastonbury festival is the largest greenfield festival globally and often referred to as ‘the greatest show on Earth!’ The festival is held at Worthy Farm, Pilton of Somerset, where Michael Eavis, the event founder, grew up and made his primary living as a dairy farmer. Michael, inspired by the Bath Festival of Blues and Progressive Music in June 1970, decided to make his own event three months later in September 1970. The festival was a success in terms of its consumer appeal; however, it made a financial loss and took five months to recuperate (Eavis & Eavis, 2019).

Nevertheless, word of mouth spread about the festival and caught the attention of Andrew Kerr, Arabella Churchill (Winston Churchills granddaughter) and John Michell (a famous esoteric writer), who had ambitions to create a festival in Glastonbury. It was at this moment where the festival embodied a countercultural ethos. For instance, the idea of the now famous Pyramid stage arose from the dream of a man called Bill Harkin (who was a friend of Andrew Kerr). Together with John Michell, who dowsed the area and determined where the ley lines were to harness the Earths energies optimally, Bill Harkin began recreating the Great Pyramid of Giza to serve as the central stage and energy centre of the festival. This gave the festival a spiritual element, connecting with the 1960s hippie movement of which the organisers (except Michael, a Methodist) were a part. Other countercultural ideas communicated included the anti-war movement, an egalitarian society, anti-capitalism and alternative spirituality, which all connected with the like-minded attendees who embodied the 1960s counterculture. To pay for the event, Michael had to get a £1500 loan and lend the deeds to his farm for the festival to go ahead. Ultimately, the 1971 festival attracted 12,000 people; Michael got his farm back, which was a huge success (Eavis & Eavis, 2019).

The 1971 Glastonbury free festival and the 1969 Isle of Wight festival are regarded (in different ways) as British versions of the legendary US 1969 Woodstock festival (Anderton, 2020). Several academics have linked the heritage of 1960s counterculture created at these famous festivals and their ongoing influence on all current outdoor rock and pop music festivals (Anderton, 2008). Other academics have also linked the 1960s countercultural movement to Mikhail Bakhtin’s characterisation of the medieval carnival (Blake, 1997; Clarke, 1982; Hetherington, 1992, 2000; Hewison, 1986; McKay, 2000; Stallybrass & White, 1986; Worthington, 2004; Jones, 2002; Anderton, 2009, 2020). During a medieval carnival, the peasantry was given license to indulge in excessive eating and drinking, sexual promiscuity, the wearing of grotesque masks and costumes, and irreverence toward those in authority. For many folks, the carnival acted as a liberation from the established order and removed hierarchy, privileges, norms and prohibitions until the close of the carnival, acting as a ‘societal safety valve’ (Anderton, 2008, p.41). Bakhtin describes this feeling of a ‘second world’ where ‘for a short time life came out of its usual, legalised and consecrated furrows and entered the sphere of utopian freedom’ (Bakhtin, 1984, p.89). It is this quote that particularly embodies the carnivalesque atmosphere of the counterculture and one that is found at the Glastonbury festival:

‘To consecrate inventive freedom, to permit the combination of a variety of different elements and their rapprochement, to liberate from the prevailing point of view of the world, from conventions and established truths, from cliches, from all that is humdrum and universally accepted.’ (Bakhtin, 1984, p.34)

With these linkages, it is clear to understand how the countercultural movement progressed from the hippie movement into the punk movement of the 70s and how these movements had lasting impacts on the history of UK culture and the Glastonbury festival. Today, the ‘Glastonbury Festival continues to be sold and experienced through a countercultural ethos of freedom, idealism, eco- friendliness, and anti-commercialism, despite a phenomenal increase in media coverage and the use of commercial sponsors’ (Anderton, 2008, p.41). They have maintained this counterculture ethos by supporting the CND (campaign for nuclear disarmament) by promoting their brand logo on top of the pyramid stage, spreading the synonymous image with the hippie movement. However, throughout the 2000s, they have begun supporting other causes such as the green peace movement and donating to Oxfam and WaterAid. The festival even takes fallow years to allow the land to recover.

Interestingly, in 2009 the managers of Glastonbury were worried about the shelf life of their festival as they were increasingly attracting middle-aged attendees. Academics suggested that more marketing efforts were needed to appeal to the younger demographics (Gelder & Robinson, 2009). However, with the introduction of late-night areas (Shangri-La, The Common, The Unfairground, Arcadia and Block9), the festival has continued to attract a young audience. The festival essentially created compartmentalised spaces to accommodate the needs of all their consumers, and in 2019 they attracted 203,500 through their gates, with a ticket price of £248. The festival has already sold out for 2022 and proves to be ever successful in the future.

‘The Glastonbury Festival aims to encourage and stimulate youth culture from around the world in all its forms, including pop music, dance music, jazz, folk music, fringe theatre, drama, mime, circus, cinema, poetry and all the creative forms of art and design, including painting, sculpture and textile art.’ (Glastonbury, 2021)

The Festival Market

Market Structure

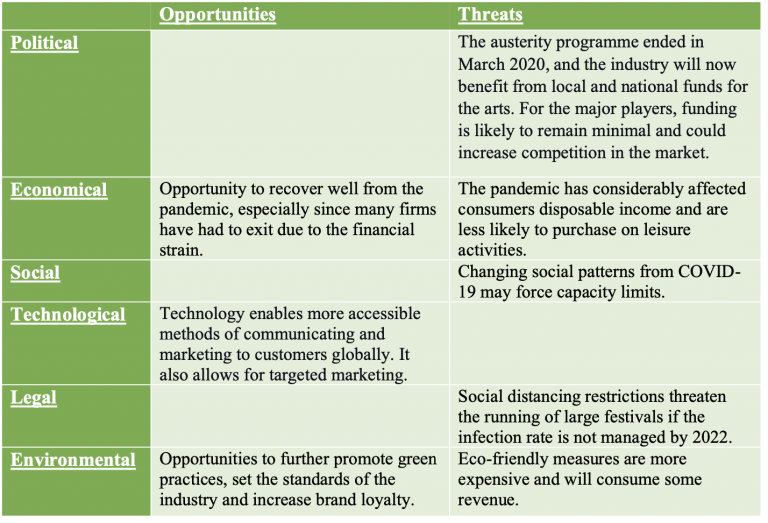

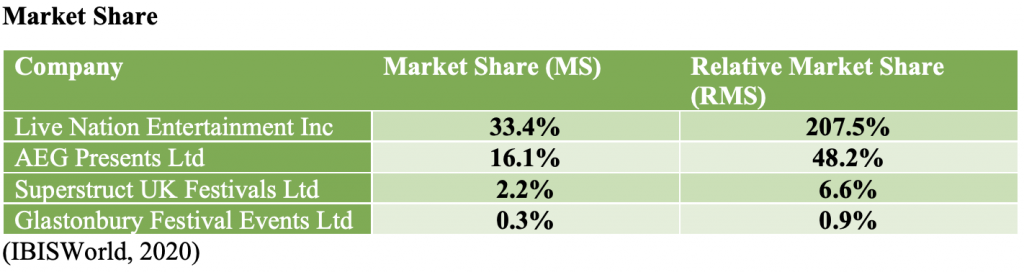

The market structure is a monopolistic competition where several firms (such as Glastonbury) have brand loyalty. The market has low barriers to entry, differentiated services (differently themed events) and a few big companies such as Live Nation Entertainment (33.4%), AEG Presents (16.1%), Superstruct UK Festivals (2.2%) and Glastonbury Festival Events (0.3%) dominate (IBISWorld, 2020).

Music events are the most lucrative in the overall market of outdoor events at 45% (see Figure 1) (BVEP, 2020). By analysing the largest festivals in the UK, it is clear to understand how Glastonbury has a strong market share. Even though the festival only runs annually (and takes a fallow year every five years), it is the largest festival in capacity at 210,000. The nearest competitor is Download Festival with 111,000, which is owned by Festival Republic, part of Live Nation. Live Nation also owns the Reading (87,000) & Leeds (75,000) Festivals and the Isle of Wight Festival (58,000). Whereas, Superstruct owns Creamfields (70,000) (see Figure 2) (Statista, 2021).

The key buyers for the industry are consumers. 70% of 2021’s industry revenue expects to be generated by ticket sales, with 30% generated by on-site services such as food and catering. (IBISWorld, 2020).

The key sellers for the industry are the major labels and independent labels, food markets and catering services. These are what makes up the content of the festivals. The other sellers are alcoholic beverage, food and tobacco wholesalers (IBISWorld, 2020).

Market Trends

One market trend is that music festivals should not focus entirely on music. ‘Festivals who rely on a specific artist to draw large crowds or the music itself may be sorely disappointed as it is equally important to create a fun and festive atmosphere that offers ample opportunity to socialise and have non-musical experiences’ (Bowen & Daniels, 2005, p. 163).

Glastonbury Festival Consumer Profile

Demographics

‘Glastonbury attracts a much older clientele with 76% of the attendees falling into the 25–34 age brackets’ (Gelder& Robinson, 2009, p.188), with only 17.6% of age groups being between 20-24 and 5.9% of the age group 15-19. Interestingly, the overall average age of attendees is 39, and that ‘over half of people attending are in a relationship or married’ (Trotman, 2018). These youthful age groups would usually be much higher at music festivals and are surprising considering Glastonbury’s aims is to ‘stimulate youth culture.’

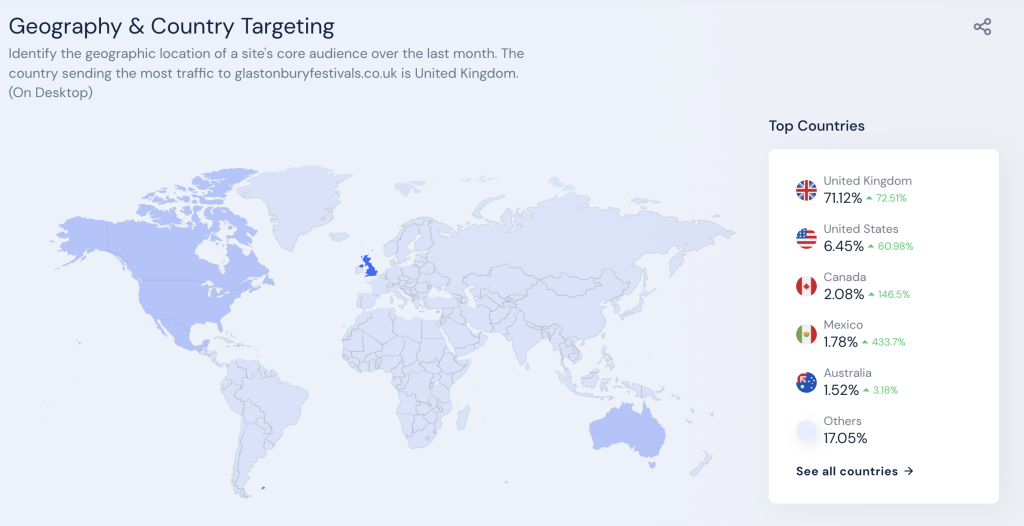

Geographics

The figure below indicates that the majority of internet traffic of Glastonbury’s official site came from the United Kingdom at 71.12%, with the United States coming second at 6.45% and Canada closely afterwards at 2.08%. The interest from outside countries contributes greatly to the live events industry as music tourism ‘generated £4.5 billion in spend in 2018, rising 13% from £4 billion in 2017’ (BVEP, 2020, p.70).

Psychographics

Motivation ‘is a state of need, a condition that exerts a ‘push’ on the individual towards certain types of action that are seen as likely to bring satisfaction’ (Moutinho, 1987, p.16).

Gelder & Robinson, 2009 recorded the consumer motives for attending the Glastonbury festival. They recorded that atmosphere and socialising with friends/family are essential for festival attendees at 19.4%. Reputation/involvement follows closely at 16.1%, and ultimately, music/artists only came in as fourth on the list of motives at 12.9%. Please see Figure 4 for the entire list of motives to attend the Glastonbury festival. This finding is reinforced by Bowen & Daniels, 2005, p.163 (see market trends).

Figure 5 shows the audience’s interests (SimilarWeb, 2021). Similar Web knows this by analysing what websites the viewer goes to after visiting the Glastonbury Festival website. The categories are news & media, music, social networks and communities, programming and developer software (questionable data) and tickets (to buy for the festival). Even though this data may not be an entire representation, it still provides a good insight into the audience’s interests.

Behavioural

Research shows that consumers are not too concerned about the festival’s content. ‘Only 14% of respondents surveyed in 2019 said they waited for the entire line-up announcement to make their purchase. Most attendees bought their tickets earlier with half or three-quarters of the line-up revealed’ (Statista, 2020). This buying behaviour is possibly due to Glastonbury’s reputation of being well organised, usually contain a wide variety of acts, and that tickets typically sell out fast. It also reinforces that consumers are more concerned with the atmosphere, socialisation and involvement over the musical line-up.

Figure 5 also gives good insight into the consumer buying process, where news and media sites can help bring awareness of the festival, music enthusiasts may look at line-ups of different festivals such as Reading Festival at the consideration/comparison stage and ultimately, the consumer ends up at the ticketing site at the sales/conversion stage (SimilarWeb, 2021).

Customer Brand Attitudes

Overall, the consumers’ attitude towards the festival looks pretty positive. The festival achieves an awe-inspiring TripAdvisor score of 4.5 with 103 views labelling it as ‘Excellent’ (see Figure 6) (TripAdvisor, 2021). On social media, the attitudes are also very positive, with many past attendees reminiscing the great experiences they had at the event and many people praising the organisers’ contribution to UK culture. However, some consumers expressed concern about how the festival has tailored the headline slots to the younger demographics. This divide is interesting as even though the festival aims to ‘stimulate youth culture’, its primary audience is the demographic range of 25-34. The festival is in a tricky position as it needs to attract new youthful audiences to ensure the festival’s longevity whilst still appeasing the needs of its core audience.

Glastonbury Festival Marketing Strategy

Brand/USP

Branding is the method of ‘establishing a distinctive identity for a product/service based on competitive differentiation from other products’ and ‘imparts meaning above and beyond the product/service’s functional aspects’ (Hudson & Hudson, 2017, p.133). For Glastonbury, its brand has been synonymously tied with the UK’s counterculture.

‘Glastonbury has become a modern event that has navigated the demands of contemporary consumerism and legislative change, whilst ever aware of the romantic, countercultural cool that differentiates it from an increasingly crowded marketplace’ (Flinn & Frew, 2014, p.421).

The quote sums up the brand of Glastonbury, with its unique selling point being its rich ties with the countercultural movement and where an attendee can experience the carnivalesque atmosphere still to this day. With the compartmentalised layout, an attendee can tailor their own experience at the festival, with the large variety of entertainment, ‘No two people’s Festival experience will be the same’ (Glastonbury, 2021).

Porters Five Forces

The Extent of Rivalry Between Competitors

Competitor Concentration and Balance – Concentration is medium.

The competition in the industry is medium and increasing. There are many large festivals, and festival-goers often only attend one per year due to the usually high cost. When the government gives events the go-ahead, the major festivals will be in high demand, forcing consumers to go for lesser well-known festivals.

Market Share

Industry Growth Rate – ‘Over the five years through 2025-26, industry revenue is forecast to rise at a compound annual rate of 77.3% to reach just under £3.3 billion’ (IBISWorld, 2020). The festival industry is in its growth stage and expected to recover well after the pandemic.

High Fixed Costs – These would be high and include subcontractors for security, crowd control, bar staff and hiring stage equipment. Variable costs would likely be for the performers/major label costs. As many festivals faced cancellations this year, it is likely to drop and return to the same levels as previous years.

High Exit Barriers – Low, as the industry’s competitors would want to acquire the festival.

Low Differentiation – Medium. Most festivals have a specific theme or are based around a particular genre to differentiate. However, the major festivals aim to be quite inclusive of all needs and tend to have a wide variety of entertainment.

Threat of Substitutes

Industry Effects – The festival industry is an entertainment industry and competes with all of its forms, especially cinemas and theatres. However, the Glastonbury Festival would never be adequately substituted as it provides a unique experience.

The Price/Performance Ratio – Festivals are a fairly costly activity compared to substitutes. However, attending a festival is a much more enriching experience that is unique and will surely prevail.

Threat of Entry

Scale and Experience – The major festivals have built up their brands, scale and reputation over

time, and a new entry would not likely achieve the same level of success.

Access to Supply or Distribution Channels – It is easy to access suppliers to hire the personnel

and equipment needed to run an outdoor event.

Capital Requirements – Is low, equipment and spaces can be rented and having the options to buy tickets early will ensure initial cash.

Power of Buyers

Concentrated Buyers – Low. Most of the revenue comes from ticket sales, which will be in high

demand as social distancing restrictions relax.

Low Switching Costs – Medium. Most festivals are differentiated and unique compared to their competitors. However, some consumers may decide to switch to a particular festival based on its programme.

Buyer Competition Threat – Low. The buyer would not have the contacts, land, permissions or a team to put on a festival by themselves that would be as successful as key industry players.

Power of Suppliers

Concentrated Suppliers – Low. Many supplier companies usually focus on a particular area, i.e.,

security, food, drinks, stage construction, and sound technicians.

High Switching Costs – Medium. A headline act could shop around and decide upon performing at the most lucrative festival. However, some acts may also want to perform at specific festivals due to their reputation/history and accept a lower wage.

Supplier Competition Threat – Low. Without the land or the contacts, the festival is likely not to be as successful.

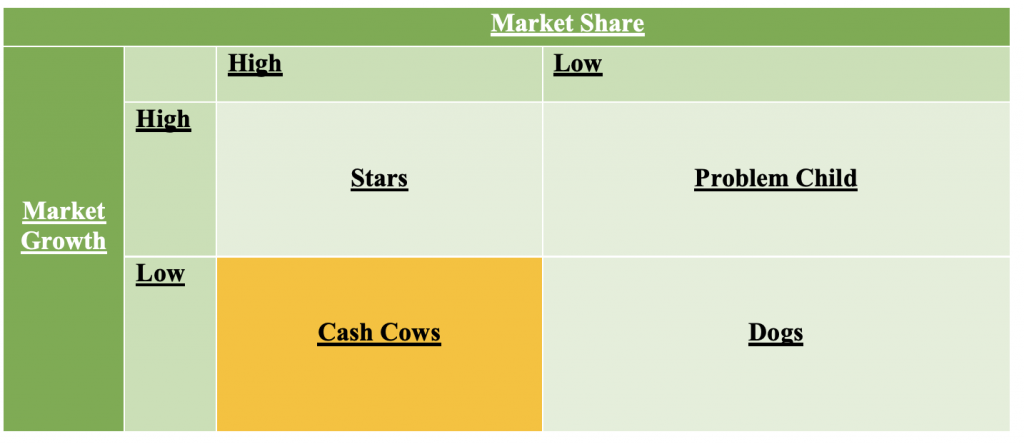

The Boston Matrix

The industry’s market growth is forecasted to be high, and as Glastonbury is the largest festival in the UK, its market share is the fourth highest at 0.3%. Currently, Glastonbury is a ‘cash cow’ as the company is mature and has already done its growth. The organisers need to be wary not to lose market share, as they risk becoming a ‘Dog’ that gets disposed of or kept in a niche.

Pricing Strategy

As shown in Appendix B, Glastonbury is the most in-demand festival, and it could charge premium prices. Therefore, a demand-based pricing strategy is best as the festival regularly sells out, and the organisers could up their ticket price to gain more profits. The ticket price for 2019 was £249, and interestingly Download (Glastonbury’s closest competitor) festivals ticket price for 2019 was £210. This price difference demonstrates that Glastonbury is already following this strategy. It can be said that the Glastonbury Festival is inelastic, where ‘demand remains relatively unaltered by price changes’ (Hudson & Hudson, 2017).

IBISWorld identified the essential CSFs to be:

The ability to sell tickets in advance of the event to reduce reliance on outside financing.

Having an excellent reputation from prior events.

Access to available land.

Easy access to clients.

Having contacts within the industry. (IBISWorld, 2020).

Glastonbury excels in all these areas, and it is no wonder that it continues to be the largest festival in the UK.

Glastonbury Festival Marketing Communications

Integrated marketing communications (IMC) is ‘the unification of all marketing communication tools (advertising, sales promotion, public relations, personal selling and direct marketing), as well as corporate and brand messages, so they send a consistent, persuasive message to target audiences’ (Hudson & Hudson, 2017, p.217). By analysing each marketing communication tools employed by Glastonbury, the extent of integrated marketing communications can be analysed.

Advertising

‘Advertising can be defined as paid nonpersonal presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, or services by an identified sponsor, using mass media to peruade of influence an audience’ (Hudson & Hudson, 2017, p.223).

Digital Methods

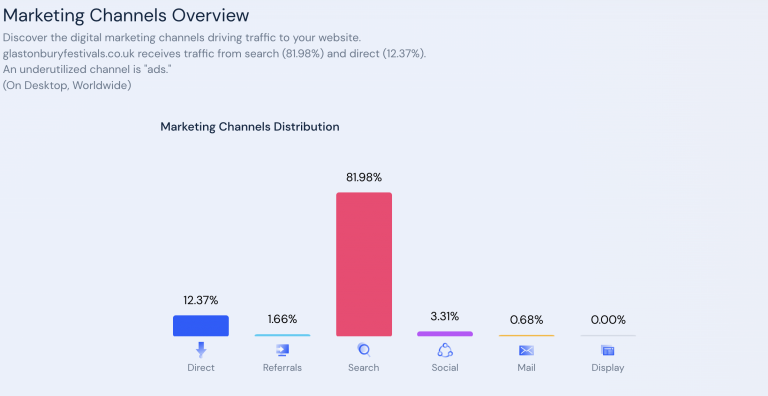

It is impossible to know how much Glastonbury spends on advertisements or if they need to advertise at all, however, the figure below suggests that they do not bring in any traffic from display ads.

The figure above shows that the Glastonbury website got 250.4K visits last month, with the majority coming from the desktop. Of that 250K, 81.98% of its traffic came from organic search, 12.37% from direct search, 1.66% from referrals (of which the majority comes from the BBC, Eventbrite and the Festival Calendar) and finally 3.31% comes through social media. With such high traffic coming from organic search, if Glastonbury needed to market the festival, they could use Google Ads and target keywords. There are currently no paid keywords detected. Nevertheless, the estimated cost for the keyword ‘Glastonbury’ would be £0.32 ($0.44), which is relatively cheap. There is currently no competition for the keyword, making it a straightforward bid for SEM (search engine marketing).

The data in this section was collected using SimilarWeb

Social Media

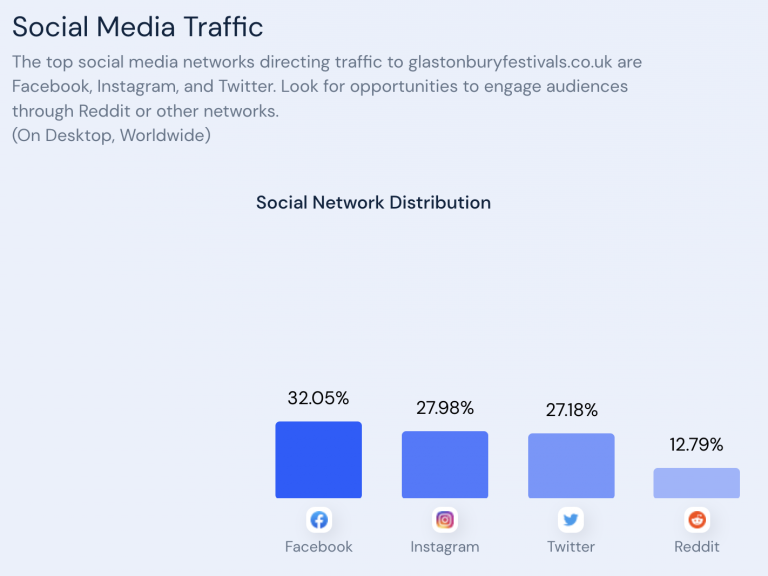

This figure below shows that most of the traffic comes from Facebook at 32.05%, with Instagram at 27.98% and Twitter closely behind at 27.18%. This majority is also indicated through the number of followers, with Facebook at 937.1K and Twitter at 730K (though Instagram falls behind at 474k). Facebooks dominance is no surprise as it is the largest social media platform that encompasses the whole demographic range.

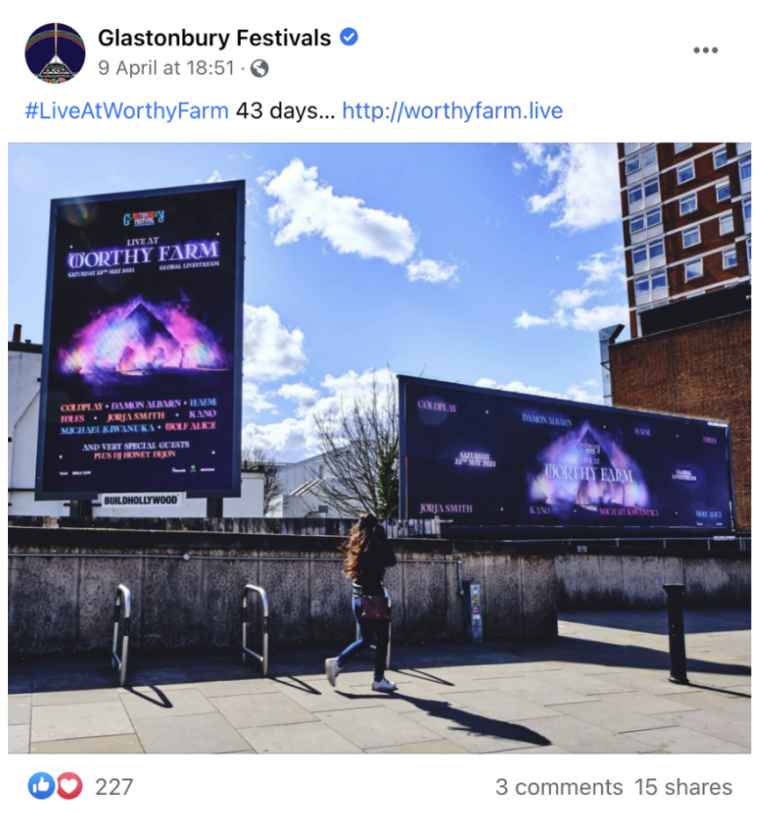

There is evidence that Glastonbury has used Facebook ads to market their 2021 virtual event (see Figure 13). Promoting a virtual event has no capacity limitations and can be advertised to unlimited people. It has a clear call to action and an aesthetically pleasing image to catch the consumer’s interest. It seems that Facebook is a great way to reach its consumers and could sell additional tickets to the festival employing the same techniques.

Offline Methods

Billboards and posters have always been the traditional way of attracting consumers to events and music-related products. It has had proven success because many people listen to music as they commute and travel. This image shows two giant billboards promoting the upcoming virtual event, and it is shared online on the official page to reach more people further.

Public Relations

Public relations is about forming a relationship with the public via communication and includes ‘maintaining a positive public presence, handling negative publicity and enhancing the effectiveness of other promotional content’ (Hudson & Hudson, 2017, p.248). In effect, PR manages the organisation’s image and reputation.

Glastonbury utilises social media to provide a digital PR presence. Through their Facebook and Twitter pages (@glastonbury, @glastofest for official news and @glastoinfo where the public can ask questions), the company can generate brand awareness, offer customer service, manage festival crises, promote the festival through content and create brand loyalty.

Content Marketing

Glastonbury promotes the festival by creating great engaging video content, which is the most engaging online format. Glastonbury is fortunate to have an archive of past performances that they can readily share online to spread awareness of the festival, and this is because Glastonbury gives exclusive rights to the BBC, whom film and record all performances. These posts tend to bring in much engagement due to people reminiscing of the great experience they had at that gig, and they form an emotional attachment as they relive the experience. Similarly, people who have not yet been to Glastonbury will see attendees enjoyment with their emotions running high and feel left out as a result. Music is ‘the shorthand of emotion’ (Leo Tolstoy) and naturally connects with people, adding to the emotional involvement within the promotional material. Another aspect of these videos is that they do not feel like promotional material as it is essentially entertainment and people get a sense of enjoyment watching them. Connecting to consumers emotions is a great way to market as emotions influence the decision-making processes of purchasing a product/service (Consoli, 2009).

Experiential Marketing

Glastonbury uses experiential marketing within its content marketing. There are five types of experience identified by Schmitt (2003). These are Sense, Feel, Think, Act and Relate. Experiential marketing focuses on the marketing function by choosing what experience(s) the consumer should feel when viewing the marketing material (Consoli, 2009). Musical videos have the power to elicit most of these responses by sensing (hearing) the music, feeling the emotions of the artist or the crowd, acting (dancing) to the music and relating (relieving the experience).

Glastonbury also uses experiential marketing to create excitement and mystery. For example, when announcing the 2019 headline act, they secretly placed a Glastonbury poster in the shop window of an Oxfam shop in Streatham. This fun and secretive PR stunt created significant interest from the public and the newspapers. The stunt was then enhanced by Glastonbury’s fan page ‘GastoWatch’ and newspaper coverage (see Figure 14). There are also other instances of secrecy and mystique, such as secret forest gigs and the secret piano bar. These messages create exclusivity, which is an experience often desired. With these tactics, the Glastonbury brand becomes a centre of emotional energy, ‘which create better relationships with potential consumers with the ability that they have to tell stories that excite (emotional brands) and integrate communication, quality, tradition (and) identity’ (Consoli, 2009, p.1000).

Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC) Analysis

Out of the five marketing communication tools, only advertising and PR are currently employed; nevertheless, if Glastonbury were short of sales in the coming years, they could utilise the other three marketing communication tools. Overall, the marketing communications all aligned with the same brand message. It was clear that the content communicated the concept of ‘experience,’ and it is particularly effective as it is what a consumer would be paying for when attending the event, a unique experience. Using experiential content and PR stunts all contribute to the arousal of excitement within consumers and acts as a form of preempting entertainment that whets the appetite before consumers arrive at the festival.

The Glastonbury Festival's Future Marketing Communications Strategy

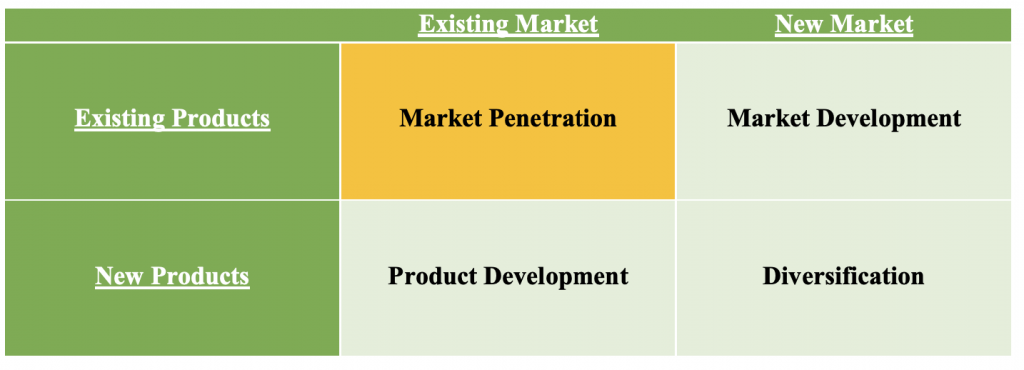

Ansoff's Matrix

The best option for growth would be to increase the market share using the same customers. Arguably, this is the strategy that Glastonbury has historically employed as the average age of the Glastonbury goer is 39. However, there is also instances of market development where Glastonbury is also attracting younger demographics. This year Glastonbury even developed a new product, the Glastonbury virtual event. If Glastonbury wanted to expand, it could do so by developing new products for different markets (virtual events, a Glastonbury revival for older demographics and a Glastonbury festival for younger demographics, or even expand to other geographical areas). However, the festival is unlikely to do this as it would ‘destroy the magic’ and raise questions of authenticity (Burgees & Hodgkinson, 2013).

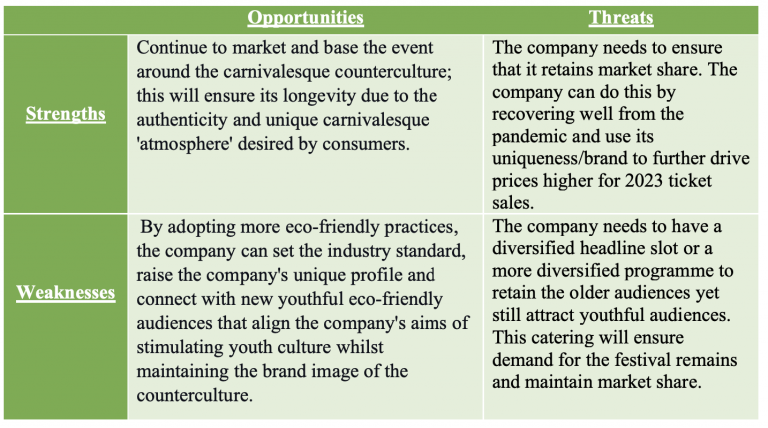

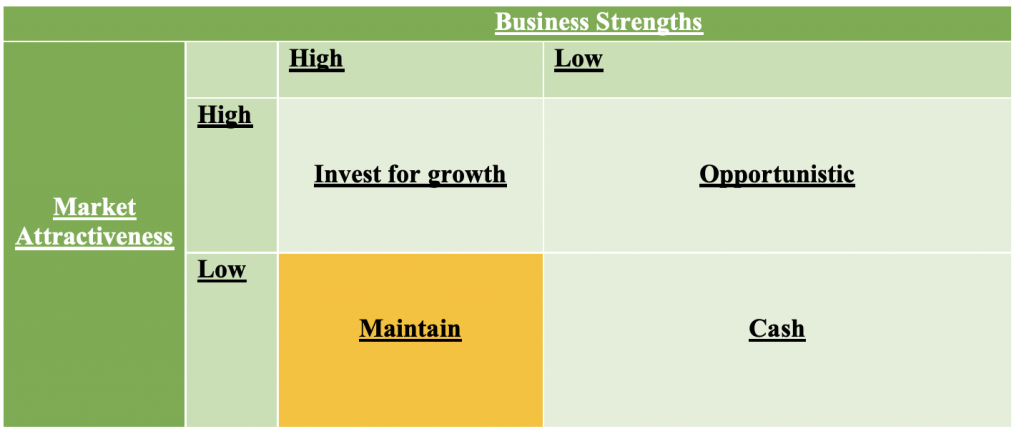

The Directional Policy Matrix - Malcolm McDonald

Glastonbury’s business strength is very high, as seen from the SWOT analysis. However, the market is currently not attractive due to the impacts of COVID-19 forcing significant changes across the industry. The current goal for Glastonbury should be to maintain its position as the UK’s favourite music festival by managing its earnings. As social distancing measures ease and as the industry recovers, the company can continue to invest for growth.

Future Communication Activities

As discussed, Glastonbury does not need to undergo extensive marketing due to its reputation and famous brand. However, if Glastonbury ever required to advertise, they could use targeted Facebook and Google Ads and increase billboard ads around cities. Currently, Glastonbury is doing everything right and needs to continue its current communication strategy to maintain its competitive position and market penetration strategy.

Conclusion

Glastonbury has built a strong brand and solid reputation over the years as a great festival, representing the counterculture’s unique carnivalesque experience. With tickets repeatedly selling out year after year, the company is in a strong position and can undergo minimal advertising to reach its ticketing sales goals. They use online methods through social media, offline methods using posters/billboards, and clever public relation stunts to ensure that the public’s interest in the festival remains high. This report brought to light the solid strategic marketing strategy of Glastonbury and provided insights into the company’s future direction. In the future, Glastonbury can continue employing its current marketing communications to penetrate the same market with its existing customers. Nevertheless, Glastonbury has options to grow as a business further, such as expanding into new products or new markets. However, Glastonbury is much more than a business. It is a legendary cultural event that stimulates youth culture while simultaneously celebrating British counterculture’s bounteous history. From its inception, it was an ethical creation made by an honest dairy farmer who had a passion for music, and it continues to this day with the same moral values. By supporting charities, the company continues its egalitarian values, and by supporting Green Peace, it simultaneously supports the counterculture. Perhaps the company will never try to be profit/market-orientated, and in doing so, it will maintain its uniqueness and exclusivity that consumers so desire.

Howard Head

I turn confused bass enthusiasts into bass gods through a simple and logical process.