May 5, 2022

Howard

- Introduction

- Research Aims

- Literature Review

3.1 Defining Music Event Types

3.11 Grassroots Music Events

3.12 Popular Music Events

3.13 Music Festivals

3.14 Music Event Infrastructure

3.2 Motivations to Attend Music Events

3.3 Differing Motivations by Segmentation

3.4 Techniques Employed

3.5 Music Festival Attendees and Popular Music Attendees - Research Design and Methodology

4.1 Research Design

4.2 Methodology

4.21 Qualitative Data Collection

4.22 Qualitative Data Analysis

4.3 Sampling - Primary Research Findings

5.1 Overview of Results

5.2 Motivations to Attend

5.3 Preventatives to Attend - Discussion of Research Findings

6.1 Discussion of Focus Groups

6.2 Music Event Motivations Comparison - Conclusion

- Recommendations

- List of References

- Appendices

10.1 Appendix 1: Brighton Focus Group

10.2 Appendix 2: Ipswich Focus Group

10.3 Appendix 3: London Focus Group

Abstract

Understanding consumer motives is an advantageous activity for event managers to undertake, and it should come as no surprise that extensive research has been conducted on music festivals within the music event literature. However, there has not been any such research carried out on grassroots events (a grassroots event generally has a small capacity and can take place in a grassroots venue, a pub or an arts space; they typically showcase the culture of the area and take risks by allowing up and coming artists to perform). This paper researches consumer motivations for attending, as well as preventatives to attending a grassroots music event. The purpose is to aid event managers to understand their consumers better so they can fulfil consumer preferences and provide better experiences to drive business. The data for this project was collected through focus groups and analysed qualitatively using thematic analysis. The findings revealed ten motivational themes: (Uniqueness; Intimacy; Being Part of a Community; The Artist/Supporting Friends; Authentic Music Experience; Good Drinks; Atmosphere; Supporting Your Local/Venue; Good Reputation; Cheap Night) and seven preventative themes (Bad Reputation; Fear of the Unknown/Intimacy; Expensive; Limited Facilities; No Good Drinks; Bad Location; Wrong Expectations). The findings indicated several consumer motivations unique to Grassroots events and gave insights into how event organisers can minimise the preventative themes. Together, these findings will aid event organisers and marketers to understand their audience better, tailor their content, and adapt their role to align with consumers’ motives to provide consumers with a fulfilling experience and hopefully prevent the closure of grassroots venues and event spaces.

1. Introduction

Cultural events have the power to validate community groups, introduce new ideas and establish new hybridised identities (Bowdin, 2010). Hybridisation is where “cultures may stay national, but what the ‘national’ is, becomes changed by global inputs” (Martell, 2017, p.21) to create a hybridised culture, which is generally seen as having a positive effect on society due to there being greater unity amongst the population. These positive impacts can be amplified when communities create, perform, listen and appraise music at an event due to their social and cultural identities being expressed (MacDonald, 2002). The cultural values derived from music events can be conceptualised as “musical creativity, cultural vibrancy and talent development,” with the social values being “social capital, public engagement and identity” (Van der Hoeven, 2019, p.266).

Music events also contribute significantly to the UK economy. The UK’s events industry is estimated to generate £70 billion, and music events constitute the second- largest contribution within the entire events industry with 17.6 billion (BVEP, 2020). In 2018, “29.8 million people attended live music events in the UK, which is a rise of 2% from 29.1 million in 2017” (BVEP, 2020, p.70), showing that the live music events industry is expanding is likely to continue to be important in the future. Many professions rely on the industry and include people within the music sector (music creators, music retailers, recorded music, music representatives, music publishing and live music), and the hospitality and transport sectors (UKMusic, 2019). Historically, music events have acted as promotional content to encourage consumers to buy an artist’s record. However, disruptive technologies and piracy removed the value of recorded music with the advent of the mp3 format and disrupted the entire industry. The recording industry now heavily relies on music events as artists can earn nearly 90% of their total income from music performances, which subsequently feeds to major labels/managers due to the ‘360 degree’ contract. For example, in 2016, Beyonce earned $54.7 million from touring, accounting for 88% of her total incom of $62.1 million (Billboard, 2016). It is understandable why the music industry would want to expand the music events sector.

Events are categorised in terms of their size; they include: (small) Local events (Grassroots venues), Major events (popular music events and most festivals), Hallmark events (famous festivals, e.g. The Isle of Wight Festival and The Glastonbury Festival) and Mega-events (where the attendance should exceed 1 million in order to clarify, and there have been no music events in the UK that have undertaken this feat) (Bowdin, 2010, Getz, 2005). Grassroot music events play a significant role in nurturing the industry’s talent by providing places for up and coming artists to gain experience, providing places for art expression amongst the community and supporting the industries infrastructure. However, due to “increased rent prices, noise complaints and lack of football”, many venues have been forced to close down, with an estimated “35% of grassroots venues closing in the last ten years” (BVEP, 2020, p.70). This downward trend has also been accelerated by the Covid 19 lockdown, where the restrictions forced the temporary shutting down of all events, then as restrictions lifted, limited business due to social distancing effecting event capacities.

Music events can also bring awareness and help ‘sell a region’ by attracting tourists, industries and investments (Liu & Chen, 2007). These events become iconic to the destination, as summarised by Homan:

“The famous jazz clubs of New York or the ‘swinging’ London night clubs of the 1960s remain vivid examples of how music venues can come to represent distinct regional experiences, as signifiers of a wider cultural milieu.” (Homan, 2011, p.105).

In London, UK, famous clubs could be The Ronnie Scotts Jazz Club, The 100 Club, The Flamingo Club or The Roundhouse.

With all of these apparent benefits that music events bring to culture, the economy, businesses and destinations through place branding and destination marketing (Getz, 2012), it is essential to understand what motives drive consumers to grassroots music events. Grassroots venues and event spaces are vital to the livelihood of the music industry and music events industry, and many are at threat of permanent closure. It would be of great importance for grassroots event managers to better understand consumer motives for attending their events so that they can tailor their programmes, make better-informed marketing decisions, and bring in more business to stop the threat of closure. Similarly, it would also be essential to understand consumers’ lack of motives for attending to see whether factors concerning consumer appeal also threaten venue closure.

2. Research Aims

There has been a significant amount of research into understanding consumer motives for attending a music festival (Formica & Uysal, 1996; Crompton & McKay, 1997; Faulkner et al., 1999; Nicholson & Pearce, 2001; Bowen & Daniels, 2005; McMorland & Mactaggart, 2007; Gelder & Robinson, 2009; Pegg & Patterson, 2010; Özdemir Bayrak, 2011; Blešić et al., 2014; Pilcher & Eade, 2016; Li & Wood, 2016; Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017; Kruger & Saayman, 2019; Brown & Sharpley, 2019; Hodak et al., 2020; Perron-Brault et al., 2020; Muhs et al., 2020), and little research into understanding consumer motives at a popular music event (Kruger & Saayman, 2012; Kulczynski et al., 2016; Brown & Knox 2017). However, there has not been any academic research into consumer motives for attending grassroots venues (that the researcher knows of). As discussed, grassroots events form a big part of the industry as they help nurture the industry’s talent; learning more about consumers will aid organisers and marketers make more informed decisions so that they can ensure the longevity of the industry. As previous studies have pointed out, events are highly differentiated and attract unique audiences particular to the unique event (Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017). Nevertheless, it would be interesting to understand the general motivations of consumers.

The purpose of this research is to (1) understand consumer motives (and preventatives) behind attending grassroots music events and (2) to understand the consumers who attend grassroots music events. For example, there may be preferences for specific demographics or geographic regions regarding their music taste, their preferences for a more culture orientated music event or a more commercialised event, or as previous studies have concluded, factors not concerning the music at all (Formica & Uysal, 1996; Crompton & McKay, 1997; Faulkner et al., 1999; Nicholson & Pearce, 2001; Bowen & Daniels, 2005; McMorland & Mactaggart, 2007; Gelder & Robinson, 2009; Pegg & Patterson, 2010; Blešić et al., 2014; Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017). After gathering data, this research’s last objective (3) is to conduct a comparative motivational analysis between the differently sized music events. The comparison will be between the primary research on Grassroots venues carried out in this paper with previous research indicated in the literature review conducted on popular music events and music festivals; it may highlight key motivational differences between the three different music event types. Ultimately, the three objectives will aid event organisers and marketers to understand their audience better, tailor their content, and adapt their role to align with consumers’ motives and hopefully prevent the closure of grassroots venues and event spaces.

3. Literature Review

This section will explore the definitions of each music event type and give clarity to the investigation.

3.11 Grassroots Music Events

The Grassroots Venues Trust provides a grassroots venue’s definition: A Grassroots venue must be 1. Considered a Grassroots venue by musicians and audiences; 2. Focus on cultural activity as its primary purpose and its outcomes; 3. Be a music business, run by music experts; 4. It takes risks with its cultural programme, and that risk-taking is the ignition system of the engine that is the UK music industry; 5. Be a beacon of music and a key generator of night-time economic activity; 6. Occupies an important role within its local community (Grassroots Venues Trust, 2021).

A grassroots music venue (GMV) may also be a pub.

“Many small venues have to have a mixed business strategy to survive— they might (be) a mix of (a) live music venue, nightclub, bar, arts centre, pub and restaurant. It is not possible to survive with only a live music business in today’s market” (Parliament UK, 2019).

The definition of a Grassroots Music Pub (GMP) encompasses the same defining factors as a GMV (see above). Another important definition is for a Grassroots Music & Art Space (GMAS). A GMAS is also characterised by the same factors as a GMV. However, where a GMV and a GMAS differs from a GMP is its amenities and infrastructure. A GMV and a GMAS must have 1. A fixed or temporary stage to facilitate music; 2. A mixing desk, a PA system and other pieces of equipment to provide live music; 3. Employs at least two of the following people (Sound Engineer, Event Booker, Promoter, Cashier, Stage Manager or Security Personnel); 4. Provides a cover charge to live music performances and incorporates promotion for the event (Music Venues Trust, 2021).

A GMV can also be categorised by their size ranging from a small venue, a medium venue to a large venue, and these are determined by their capacity, activity, employment and financial return (Music Venues Trust, 2021).

For the purpose of this study, this research will class a Grassroots Music Event, a music event that takes place at either a GMV, GMAP or a GMP.

3.12 Popular Music Events

Popular music is defined as music that is “mass produced, mass marketed, and is generally treated as a commodity” (Kotarba & Vannini, 2009, p. 9). As this sort of music has a broader appeal due to it being mass-marketed, the events tend to be much more significant in their capacity, stage production and scale. To please a wider audience, they include a significant focus on aspects other than music (such as visual effects and stage production). This knowledge was inferred from research completed by Brown & Knox, where they said, “such music are actively seeking out dazzling visual aspects in what would still be expected to be a predominantly auditory experience” (Brown & Knox, 2017, p.242).

3.13 Music Festivals

“Traditional conceptions of popular music festivals describe collective events in which ritual, celebratory and experiential elements converge in order to provide audiences with entertainment and knowledge” (Paleo & Wijnberg, 2006, p.51). This definition perhaps refers to older festivals where music was not the event’s focus, but a community celebration of the harvest or other calendar events were. The most famous music festivals were The Woodstock Festival 1969, The Isle Of Wight Festival 1969 and The Glastonbury Fayre 1971. These festivals all embodied the 60s countercultural ethos, and several academics have linked the heritage of 1960s counterculture created at these famous festivals and their ongoing influence on all current outdoor rock and pop music festivals (Anderton, 2008). Due to the countercultural ethos being such a strong influence on modern-day music festivals, this research will explore the phenomenon of the countercultural and the carnivalesque. For instance, academics have linked the 1960s countercultural movement to Mikhail Bakhtin’s characterisation of the medieval carnival; the following articles were cited by Anderton (Blake, 1997; Clarke, 1982; Hetherington, 1992, 2000; Hewison, 1986; McKay, 2000; Stallybrass & White, 1986; Worthington, 2004; Jones, 2002; Anderton, 2009, 2020). During a medieval carnival, the peasantry was given license to indulge in excessive eating and drinking, sexual promiscuity, the wearing of grotesque masks and costumes, and irreverence toward those in authority. For many folks, the carnival acted as a liberation from the established order and removed hierarchy, privileges, norms and prohibitions until the close of the carnival, acting as a “societal safety valve” (Anderton, 2008, p.41). Bakhtin describes this feeling of a “second world” where “for a short time life came out of its usual, legalised and consecrated furrows and entered the sphere of utopian freedom” (Bakhtin, 1984, p.89).

Modern-day festivals are, however, highly organised and include compartmentalised zones whereby an attendee can tailor their own experience at an event; according to organisers from The Glastonbury festival, “No two people’s Festival experience will be the same” (Glastonbury, 2021). It could be said that some festivals have held onto their cultural heritage, whereas other festivals have more of an economic motive to their creation that facilitates the various performances of artists to consumers.

3.14 Music Event Infrastructure

The infrastructure of music events allows the development of musical artists. From a grassroots level, artists can learn their craft and gradually build up a following playing to larger capacities, to then getting recognised by A&R representatives who sign the artist up with their label and market their music, to where they ultimately get to play at popular music events and festivals when the artist has reached a massive following.

It is “crucial that there are live music venues of all sizes, from back rooms in pubs to medium-sized venues, through to large arenas such as Wembley. If one link in the chain is broken, it endangers the fragile infrastructure that supports our successful live music industry” (Cluley, 2009, p.19).

3.2 Motivations To Attend Music Events

Motivation “is a state of need, a condition that exerts a ‘push’ on the individual towards certain types of action that are seen as likely to bring satisfaction” (Moutinho, 1987, p.16). The motivations may be utilitarian (a functional need) or hedonic (an experiential, emotional need) and can vary in certain degrees of strength depending on what the consumers goals are (Solomon et al., 2019). A ‘need’ is classified into biogenic needs (necessary for survival) and psychogenic needs (i.e. status, power, affiliation), of which the latter “reflects the priorities of a culture” (Solomon et al., 2019, p.169). Motivations can be a powerful precursor to consumer buyer decision making and satisfaction (Crompton & McKay, 1997; Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017). By identifying consumer motivations, an organisation can tailor their product/service and promotional content to align with its audience’s needs. By considering the consumer, the company will attract more business and ensure the continued survival and future growth if the consumer is satisfied with the product/service and likely to return (Kim, La Vetter, & Lee, 2006).

The majority of previous studies have focussed on finding the consumer motivations in music festivals. A music festival is a period of celebration within a community, where music is the primary attraction of celebration (Bowen & Daniels, 2005). However, music festivals are very differentiated due to their local origins and sometimes offer multiple attractions. For instance, in the literature, the Fiesta Festival (Crompton & McKay, 1997) is a parade with musical elements, and Celebrate Fairfax (Bowen & Daniels, 2005) is a county fair and a music festival. Another differentiation is the genre, The Umbria Jazz Festival (Formica & Uysal, 1996), The Tamworth Country Music Festival (Pegg & Patterson, 2010), Efes Pilsen Blues Festival (Özdemir Bayrak, 2011), The Purbeck Folk Festival (Pilcher & Eade, 2016), The Macao International Music Festival offering western classical music (Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017), the jazz festivals in South Africa (Kruger & Saayman, 2019), Electronic music festivals (Hodak et al., 2020) and Defqon.1 weekend festival providing rave music (Muhs et al., 2020). Festivals can also be quite inclusive and known for having a varied programme to attract a wider audience, with the literature including Storsjoyran Music Festival (Faulkner et al., 1999), a local festival in New Zealand (Nicholson & Pearce, 2001), The Glastonbury Festival and V Festival (Gelder & Robinson, 2009), EXIT Festival (Blešić et al., 2014) and MIDI Festival (Li & Wood, 2016). Other literature analyses music festivals linked to geographic locations, such as local Scottish music festivals (McMorland & Mactaggart, 2007), UK music festivals (Brown & Sharpley, 2019) and Canadian music festivals (Perron-Brault et al., 2020). Each festival has unique consumer motivations as each festival is unique due to the culture, geographic location, genre focus and the need to be strategically differentiated in the competitive festival industry.

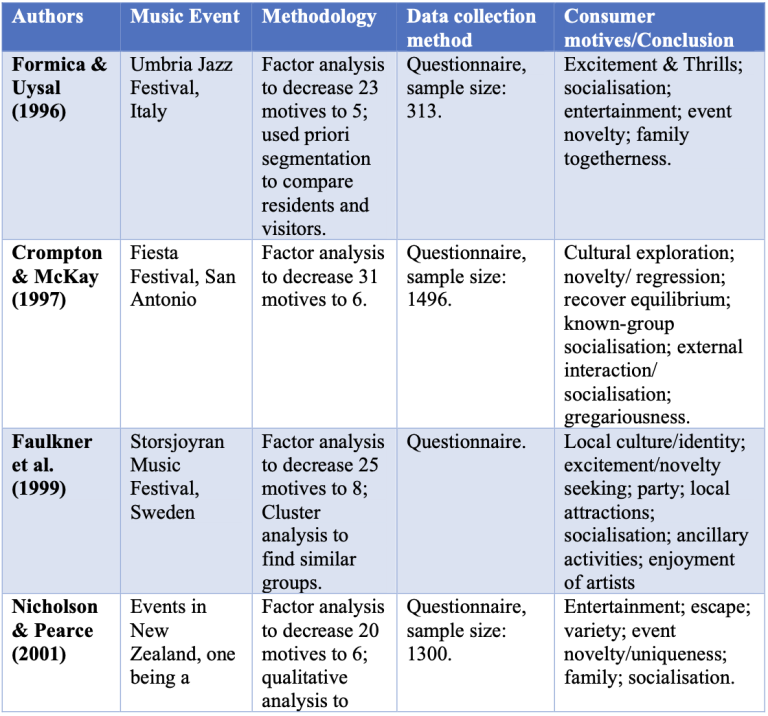

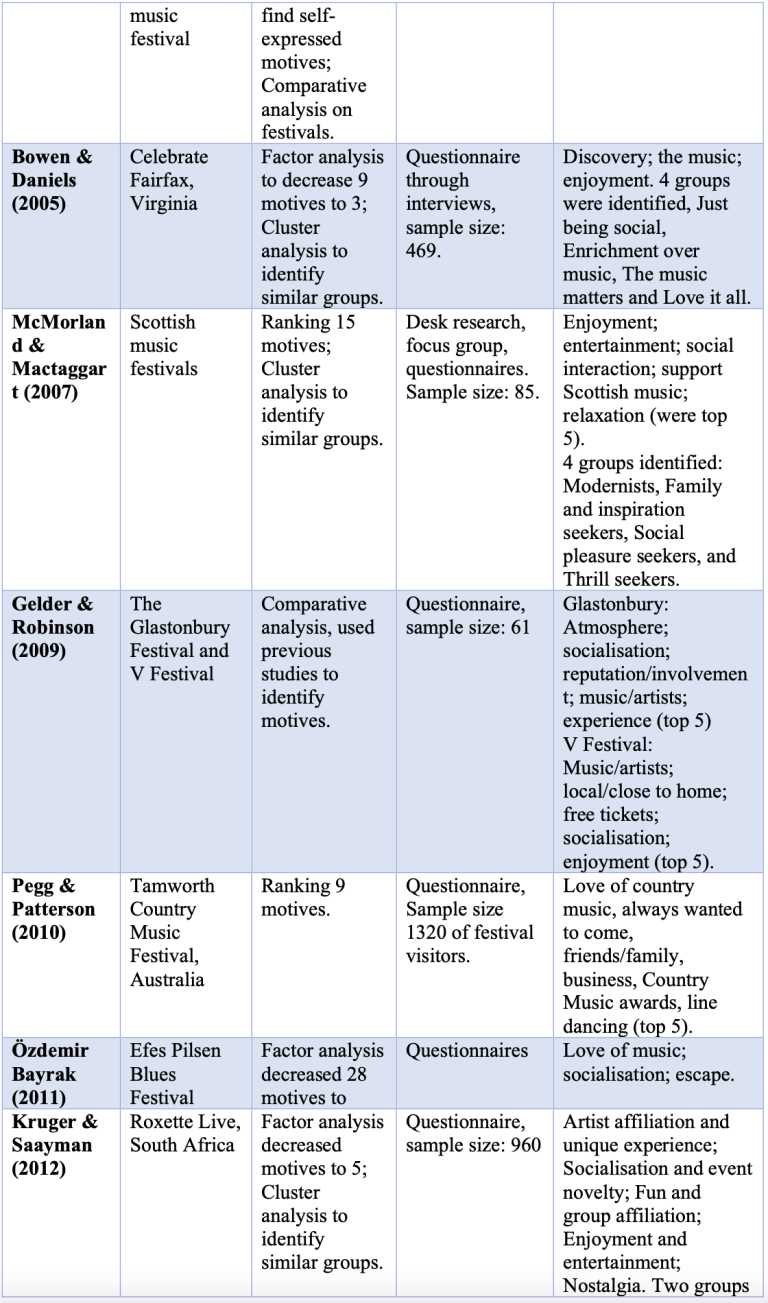

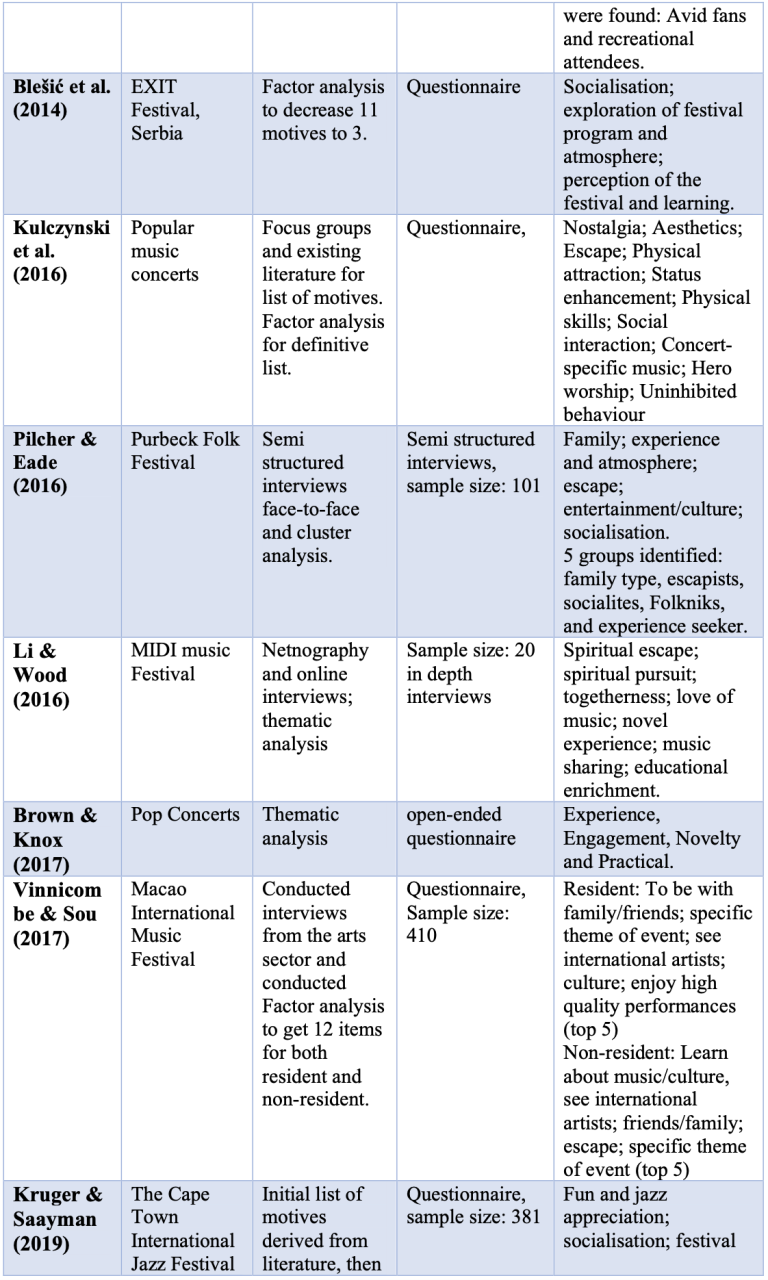

Each study is summarised in Table 1, detailing the authors, event type, methodology, data collection method and the concluding consumer motives unique to that event. The articles were found using advanced search of ‘motivations’ and ‘music festival,’ ‘music event’ and ‘grassroots music venue.’ Overall, the underlying common consumer motives were: event-specific/music; family/known group socialisation; escape and relaxation; event novelty; excitement and enjoyment; cultural exploration; and socialisation (Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017). When designing this paper’s research, these overlying motivational factors will be considered and compared when analysing the different music event types.

3.3 Differing Motivations By Segmentation

Many festivals and events have a local origin, and “it is only later that some events take on the additional role of attracting visitors to an area, while still maintaining their original function of meeting resident needs” (Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017, p.275), and this is expected because as the business grows, so does its consumer reach. Some studies understood that motives were likely to differ regarding group and market, for instance, segmenting their consumer motivations by residents and non-residents (Formica & Uysal, 1996; Vinnicombe & Sou, 2017).

Table 1: Literature Comparison

Other studies sought to discover homogenous groups by undertaking cluster analysis (Faulkner et al., 1999; Bowen & Daniels, 2005; McMorland & Mactaggart, 2007; Kruger & Saayman, 2012; Pilcher & Eade, 2016; Perron-Brault et al., 2020). The cluster analysis brought great insights into the specific groups who attended and provided valuable marketing information. There has also been some research into festival segmentation by looking into the socio- demographic of consumers (Brown & Sharpley, 2019; Kinnunen et al., 2019). This information also proves to be highly valuable in better understanding consumer groups for marketing purposes. Undertaking cluster analysis will be advantageous in this research to better understand the segmented groups attending various music event types, especially grassroots venues; however, this would be a significant undertaking.

3.4 Techniques Employed

The majority of previous research methods included making a list of possible consumer motivations, which were then reduced to a shorter list using factor analysis. The initial list of motivations was obtained from previous research or explored conducting focus groups, distributing questionnaires, undertaking interviews with industry experts or online interviews and using thematic analysis to find discussed commonalities. Factor analysis is “a set of multivariate statistical methods for data reduction, and for reaching a more parsimonious understanding of measured variables by determining the number and nature of common factors needed to account for the patterns of observed correlations” (Hayton et al., 2004, p.192). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is advantageous when there is little theoretical basis. As events are unique, and as there is little research in the area, it is apparent why previous studies adopted the method.

The majority of research used questionnaires containing the consumer motivational items found from thematic analysis. Qualitative data was quantified using seven scale Likert scales (some in-person studies used a five scale Likert scale so that the questionnaire would take less time and be less obtrusive to festival attendees) and then analysed statistically. Studies that wanted to carry out socio-demographic analysis, cluster analysis and segmentation tailored their questionnaires to include basic information about the individual. These included age, gender, domicile, education, socio-economic group, social class, annual income and music event specific questions such as preferred genre (Kinnunen et al., 2019), and thoughts around entertainment, service, engagement, added value, festival image and ethics (Brown & Sharpley, 2019). Some studies also adopted a qualitative approach to their questionnaires by containing open questions (Faulkner et al., 1999; Nicholson & Pearce, 2001; Gelder & Robinson, 2009), which significantly helped generate event specific motivations.

3.5 Music Festival Attendees and Popular Music Attendees

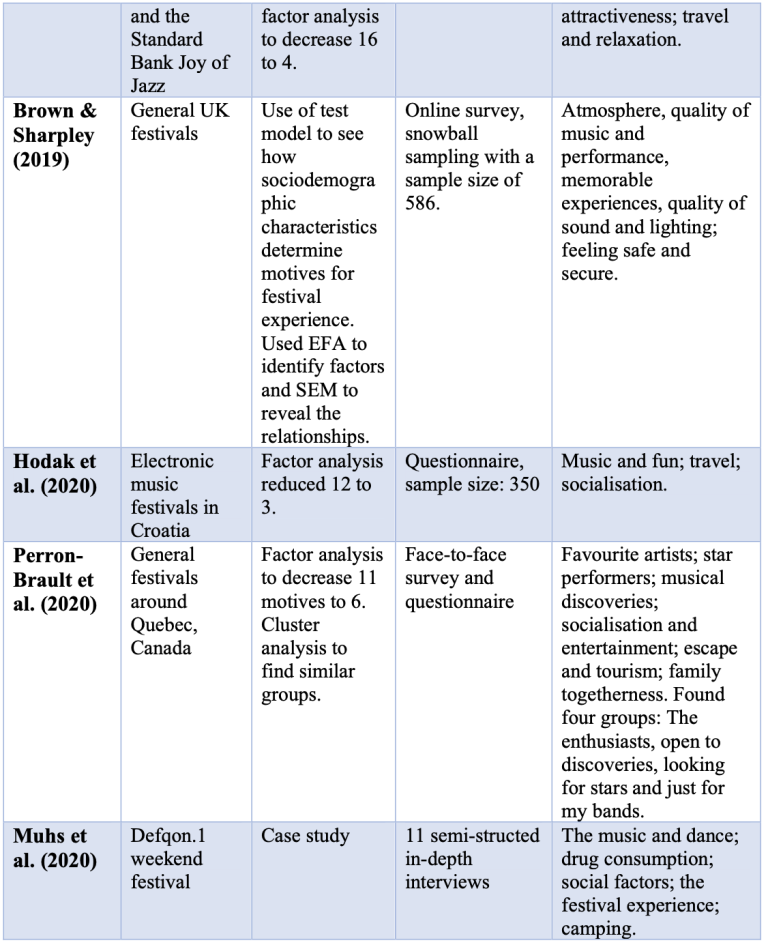

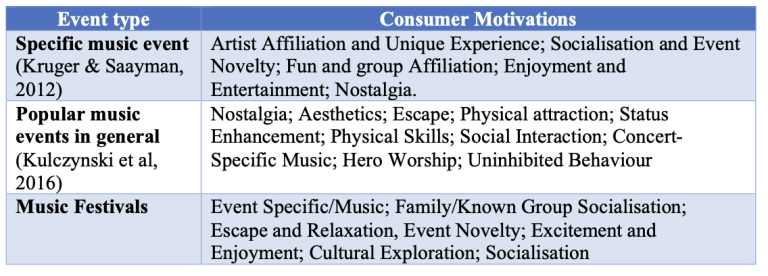

There were considerably fewer research papers regarding popular music events. More research is needed to understand consumer motivations in this area, especially since this is the most lucrative event type for performing artists. However, Table 2 compares the available literature for consumer motives behind attending a specific musical artist (The South African Roxette Tour), popular music events (in general) and music festivals (as discussed in 3.1).

Table 2: Popular Music Event and Music Festival Consumer Comparison

Kruger & Saayman, 2012 undertook cluster analysis and found two groups that help explain the differences in motives: ‘Avid Fans’ and ‘Recreational Attendees.’ The consumer motives such as nostalgia and having a stronger focus on specific music and artist (hero worship) was found to be a more significant focus with ‘Avid Fans,’ whereas ‘Recreational Attendees’ have more general entertainment motives. There is evidence that these two groups are identified in attending festivals. For example, “according to research from Ticketmaster, 45% of festivalgoers attend a festival for atmosphere, while 42% go for the line-up” (UKMusic, 2019). Perhaps ‘Recreational Attendees’ have stronger motivations for the atmosphere, whereas ‘Avid Fans’ have stronger motivations which are more specific when it comes to music and artists, and would therefore tend to wait for the line-up. Perhaps it could be said that as music festivals have become embedded into UK culture, they attract more ‘Recreational Attendees’ than ‘Avid Fans’ due to festivals having multiple areas of attraction. The levels of ‘Recreational Attendees’ possibly decrease as the music event type becomes more specific in terms of their artist/genre, where ‘Avid Fans’ possibly increase. Gaining a broad view of music event types will aid in discovering more about this phenomenon and will be explored in the latter stages of the data analysis, where hopefully, more comparisons can be made after generating data into grassroots venue consumers.

4. Research Design and Methodology

4.1 Research Design

This research acknowledges that motivations are personal and derived from humans, and that humans are different from physical phenomena because they create meanings. This research, therefore, takes on the interpretivist philosophy and is appropriate as motivations will differ from person to person. As there is no literature on consumer motivations behind attending grassroots venues, the research will be inductive and exploratory. This research has chosen a solely qualitative approach in data collection and analysis.

4.2 Methodology

4.21 Qualitative Data Collection

As found in the literature review, the preferred research method was gaining qualitative data (through focus groups, interviews, questionnaires and surveys). Due to the covid pandemic and lockdown restrictions, the live music events industry is on hold until deemed safe for the public. The lack of music events made it impossible to undertake face-to-face interviews and focus groups with event attendees. However, online methods, such as distributing online questionnaires to relevant audiences/social media group pages, were a viable option and was a method previously employed (Li & Wood, 2016). Nevertheless, this research chose to undertake online focus groups targeting specific places and demographics to discuss and explore possible motivations for attending grassroots venues and the lack of motives for attending grassroots venues. This qualitative method is appropriate as open discussion conveying participants thoughts and feelings is needed to explore the phenomenon. Prior to commencing the research, full consideration was made regarding research ethics (such as contacting participants using the universities’ secure email, not asking deeply personal questions or bringing up anything that could irritate participants), which minimised the harms and risks associated with my participants. All participants identities were anonymised, with names stripped. This privacy protected the participants, and the confidentiality allowed them to fully express themselves, knowing that their identities would not be disclosed (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). Only individuals who were above eighteen and had experienced a grassroots music venue was allowed to participate. During the initiation phase, all possible candidates were given a consent form outlining what they could expect from the session, as well as a detailed definition of grassroots events to clarify whether they had experienced one or not. Participants were politely excluded if they did not meet the criteria as the data would not be credible if a participant gave their thoughts on something that they had not experienced. The moderator asked the same open questions across the focus groups and allowed the conversation to flow so that the attendees could comfortably express themselves. The discussions were video recorded (only after permission to do so by all attendees) and later made into a transcript, which was viewed solely by the moderator to protect all participants identities. The focus groups duration lasted until the group felt they had fully explored their motivations and preventatives to attend a grassroots event. The focus group durations were: Brighton Focus Group – 00:49:24; Ipswich Focus Group – 00:28:44; London Focus Group – 00:42:25.

This research method had the possibility of producing inaccurate data, by participants desires’ to please the moderator/research assistant or to change their answer to be socially desirable (Saunders et al., 2019). However, the benefits of focus groups far outweighed the disadvantages and videoing the focus group sessions also aided in mitigating any of these effects when reflecting upon the videos. See ‘Appendices’ to view the final transcripts.

4.22 Qualitative Data Analysis

This research employed thematic analysis on the focus group transcripts.

“Thematic analysis is a qualitative research method that can be widely used across a range of epistemologies and research questions. It is a method for identifying, analysing, organising, describing, and reporting themes found within a data set” (Nowell et al., 2017, p.2).

The analysis took place on a computer-aided qualitative data analysis software (NVivo). The thematic analysis process had six steps: 1. Familiarising the data; 2. Generating initial codes; 3. Searching for themes; 4. Reviewing themes; 5. Defining and naming themes; 6. Producing the report (Nowell et al., 2017). As this is exploratory research, the research undertook an inductive approach and developed codes using descriptive coding and In Vivo coding, where themes emerged in an exploratory manner.

4.3 Sampling

Thematic analysis is beneficial, as it allows the moderator to check through the transcripts and determine the moderator’s effect on the data and determine if any bias affected what the participants said; it allows the researcher to see their reflexivity (Dodgson, 2019). For readers to understand the trustworthiness of the data, this research identifies the researcher (Moderator in the transcripts) to be a white man in his early twenties, who is originally from the countryside and a musician.

When selecting participants in the focus groups, the researcher reached out to acquaintances of family members, staff and friends who attended live music events regularly (or used to attend regularly). Participants were chosen and grouped by their age range in their geographical region to see if different ‘clusters’ would yield different results. The participants were grouped into three focus groups according to their town/city and age range: Brighton Focus Group – Demographics Aged 40-60, Ipswich Focus Group – Demographics Aged 40-60 and London Focus Group – Demographics Aged 20-30. The purposive sampling was beneficial in finding the right participants and the acquaintances created a talkative and comfortable atmosphere where they could express themselves fully.

5. Primary Research Findings

5.1 Overview of Results

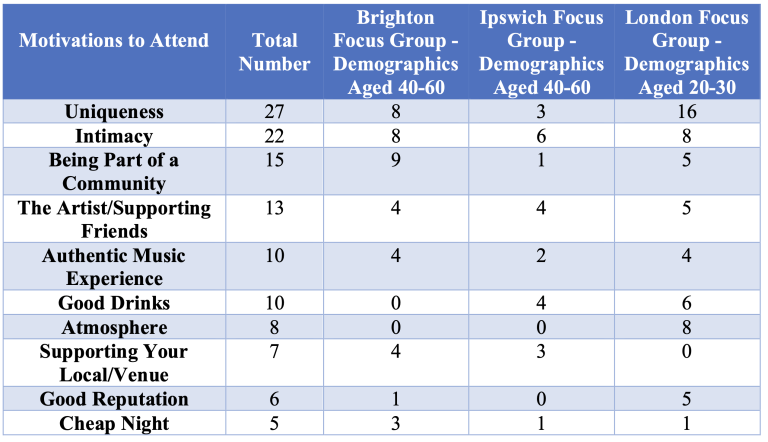

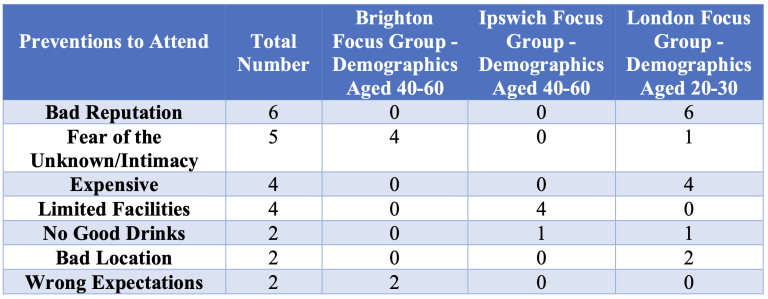

The results identified ten motivational themes to attending and seven themes linked to preventing somebody from attending a grassroots event. The findings indicated that Uniqueness, Intimacy and Being part of a Community were the top three motivational themes to attend, and that the top three preventative themes to attend were Bad Reputation, Fear of the Unknown/Intimacy and Expensive. Interestingly, one of the highest motivations to attend (Intimacy) may also be a preventative measure if someone has not experienced that particular environment before (Fear of the Unknown/Intimacy). The findings indicated that each group had their own preferences and unique views, though some themes were not discussed in every focus group, and this is represented with a zero in the table.

Table 3: Motivations to Attend – Results

Table 4: Preventions to Attend – Results

5.2 Motivations to Attend

This research will now explore each motivational theme in detail:

Uniqueness

The focus groups revealed that this was one of the most important themes. A key code from this theme was the idea of spontaneity, surprise, curiosity and that of the unexpected.

Speaker 3, Brighton

“One of my motivations…was the character that runs the night. A guy called Andy Hank dogs. His band was called The Hank Dogs. And so, and he was such an entertaining character, it didn’t really matter who was playing there…I had many friends that came along with us who they went for the sheer entertainment. I mean, it was like a variety show. But there was a guy one night who got up on stage with no instruments and said he made indigenous noise vibrations and he just did this with his mouth. He made a sound like a didgeridoo and managed to do a full set and captivated the audience. I mean people were all jaw dropped ’cause the guy was so good at it! But it was about the sort of the night you know… This sort of curiosity as well each week to see, you know, what was going to happen the following week.”

This quote perhaps sums up that his motivation was to see a creative and charismatic event manager who kept captivating audiences through unique entertainment each week. It is the reason why events are highly differentiated at the smaller event level. Much like there is a motivation to witness a musician be creative and improvise on the spot, there could be a motivation to see the creativity behind an event manager, who actively creates, adapts and adds to the event as it unfolds. Though, the overall codes here was uniqueness and curiosity.

This theme is also reinforced:

Speaker 4, London

“Again, it’s that thing with grassroots venues, it’s the story! Yeah is it close? Is it gonna be a good vibe? Is there mates going? Are you gonna have a ******* epic night?”

The audience has an input and contributes to the event’s success and the overall enjoyment of all involved. This theme is unique, as larger music event types are much more choreographed, scheduled and strictly organised, where the audience has less of a participating role.

Speaker 3, Brighton

“I used to have a fire, and friends just used to come, sit and play. I think it was very…the word authentic comes to mind. So what you were saying with the bigger venue…you’re connected, but perhaps there’s more authenticity in that intimate exchange you have with people when they’re right in front of you. Whereas at a bigger venue, nowadays lots of things are pre-recorded and (I wrote a little bit about this) about managed spontaneity. I like the spontaneity of a gig where somebody can make a mistake and fluff it, or just break out to something else, somethings not working for them, so they start off on something new. Those things for me, are really the magical moments, which often you can’t get a bigger gig. The fireside is the ideal place as you have got that close proximity to each other, and to the source or whatever sort of music entertainment it is. So I think authenticity is something about the Grassroots venue which is most important. You get the real experience, it’s up close, and quite intimate.”

This quote is very much linked to ‘Intimacy’ and ‘Authentic Music Experience’ themes. However, the idea of spontaneity perhaps enhances these other themes.

The idea of ‘having a theme around a night’ was particularly important for the London Focus Group, and how a theme can help differentiate an event from others by having a unique selling point. For instance: “If they’re doing a foam night! Or a ball pit night” (Speaker 3, London).

A unique selling proposition (USP) can help motivate consumers to attend. Other USPs included a ‘metal night’ and a ‘drag night.’ It could also be said that a particular artist is a USP to the event if they are known (John Mayer, U2, Robert Plant, GreenDay, Area 11, and Roachford were all expressed). Any of the other nine motivational themes could also be a unique USP to a grassroots music event.

The uniqueness theme also gave insight into how a grassroots event can yield a different and unique experience than other music event types. Furthermore, this code is also linked to the themes of ‘Intimacy’ and ‘Authentic Music Experience.’

Speaker 4, Ipswich

“I’d rather a more intimate…grassroots venue to get that better live experience than a stadium.”

Speaker 1, Ipswich

“It is just a little bit of a different place to go. Invariably, you know it’s sometimes not a pub, could it be a pub? But it’s just got some character, hasn’t it?”

These quotes again link to the codes of the unexpected, story, character and uniqueness.

Intimacy

The Intimacy theme links to Uniqueness, as big popular music concerts and music festivals are too big for intimacy to occur regularly. Moreover, it is this attribute of grassroots music events that make it a preferable environment.

Speaker 1, London

“You can have a small group of high quality, engaged people, its a much more energetic and biting environment.”

This quote links to the Atmosphere theme where intimacy contributes significantly to the environment.

Speaker 2, London

“Yeah. When you’re in a small venue, everyone has that kind of live or die…kind of mentality, of like I’m here and I just want to absolutely give my soul to the whole ******* place.”

A smaller and intimate environment is better for music fans.

Speaker 2, London

“You’re much closer to the artist, but also much closer to the fans who are like super into it.”

Speaker 3, London

“It’s almost like a concentration of the front row of a major festival or major gig in one place.”

Speaker 3, Ipswich

“And all of the artists walked past all the audience to get onto the stage. So you’re very, talk about up and close and personal. It is up and close and personal. Now at the end of their performance, you just can go and stand and talk to them, so that it’s really that close and personal.”

These quotes about Intimacy support the Uniqueness theme, as they are experiences unique to smaller events. An interesting concept of house concerts was explored in the Brighton focus group. A band would perform in someone’s conservatory or basement and temporarily transform their home into a grassroots music and arts space, which provided a unique experience, especially an even more intimate setting.

Speaker 2, Brighton

“There’s no distance between you and the performer, it’s very intimate and a lot of them perform acoustically, so they don’t have any mikes or anything like that, and some do. But a lot is just, you know, voice and guitar. It’s great!”

Other temporary music spaces were also discussed, such as a ‘fire circle,’ ‘community centres transformed into a music venue’ and of course ‘pubs.’

Being Part of a Community

This theme was a motivation where the music was less critical, and the people who attended these events were more of an attraction.

Speaker 3, Brighton

“It was about going to hang out with sort of like-minded people really… it didn’t really matter what band was playing, as long as there was a band playing and there would be those people, the crowds that would hang out there. If there wasn’t a band on, there’d be, you know there’d be a DJ or a jukebox playing, so you’d still get the music element.”

This ‘communitarian’ aspect involved similar codes such as ‘socialising,’ ‘being part of something new,’ and ‘going for the community.’ It could also be said that the theme ‘Supporting Your Local/Venue’ is also linked to communitarianism, where a music event is a place where the community gathers to support one another.

This theme also links to ‘Atmosphere.’

Speaker 4, London

“I respect the atmosphere, but for me, It’s the people around you that create that atmosphere” (Speaker 4, London).

A notion was put forth that it was the people within the venues that made them exciting and unique places to be.

Speaker 1, Brighton

“It wasn’t a sort of glamorous music scene, but it was the crowd that was there and a feeling of it being an emerging fashion, lifestyle, scene that was attractive that I wanted to be part of.”

This idea of being part of a community that together experiences something exciting, new and unique is echoed in the London Focus Group.

Speaker 4, London

“Yeah, is there something unique about the place? Do you have history there? Or do you want to make history there?”

The Artist/Supporting Friends

Participants expressed that a particular reason for their attendance was because they researched the artist performing.

Speaker 3, London

“Yeah, for example, earlier this week there was a Homeblood concert at The Boileroom in Guildford. You had to have a £15 entry fee, and I think £15 pounds, £12 pounds…and you had to have a lateral flow test, which is a lot you know in terms of inconvenience. So anyone who turns up at that gig. Watching, bouncing and jumping along to Homeblood is very, as equally committed to the next person. You’re not going to that gig passively or just because you’ve wandered by. You’re going there because you have intention to go and see that band on that night.”

Speaker 3, Ipswich

“I would say the same as [Speaker 1], that we would do some sort of research first to say that, we’re going to see such and such a band at this venue.”

Participants also expressed that they went because they knew the artist/musicians performing or knew who worked at the venue.

Speaker 3, London

“I will only go there because they somehow managed to scrape together a decent reputation whereby they have some good local bands, including [speaker 5] for example, when you played with The Night Society I was down there in a heartbeat. And I had a mate from Andertons who was doing a three piece there back in the day. I was there in a hurry. I wouldn’t ever, in a million years choose to go there for a night out.”

These motives have a clear intention for why people went to these events.

Authentic Music Experience

It was expressed that grassroots events provide a better and more authentic music experience than other event types due to the intimacy, size and nature of grassroots events. There were several reasons why, such as:

Speaker 2, London

“Well, you can lose yourself more.”

Speaker 3, London

“Yeah, it’s like you feel more significant, I think as someone who’s watching.”

Speaker 3, Brighton

“I think authenticity is something about the Grassroots venue which is most important. You get the real experience, it’s up close, and quite intimate.”

To give more weight to this idea is that many famous artists go back to play at Grassroots venues even though they probably make less money and sell fewer tickets as the grassroots capacities are more miniature than large venues they typically perform.

Speaker 4, London

“It’s kind of like a step back in time, because there’s no way that you get a John Mayer usually in a venue with a 100 people, it’s incredibly unique.”

These also add to the uniqueness theme. As grassroots venues hold a smaller capacity, the tickets are much rarer and more sought.

Speaker 3, Brighton

“There seems to be thing for bigger artists to go back and play at more intimate, smaller venues. U2 did a thing a few years ago now in The Apollo. And it was a relatively small venue compared to their 80,000 seat stadium they play in. And the buzz around the fan community about that gig…the tickets were like gold dust for people to get there and be part of that. They’ve played at other small venues, like in New York, where they wouldn’t normally get the chance to do that sort of thing. It was underground, quite sort of secretive, and these things emerge a couple of days beforehand that they’re playing at this sort of venue. It usually gets sold out, and unless you’re in the know, you miss out.”

Good Drinks

This theme resonated highly for the London and Ipswich groups.

Speaker 4, London

“If they have Guinness, yes I’ll go. If they don’t have Guinness. Hmm yeah, hold that one.”

Speaker 2, London

“I’m going to spend loads on the drinks, that’s why I’m there, you know?”

Speaker 3, Ipswich

“And certainly, they certainly need drink there. I’m not so much worried about food. But you know, they sort of go hand in hand, drinking and watching music.”

Speaker 2, Ipswich

“It’s good if they got some decent beers on as well.”

Having a good selection of drinks at an evening event is undoubtedly essential, especially when music is involved. Some participants expressed that it would prevent them from attending if the venue did not have drinks or even a specific brand of drink (Guinness).

Atmosphere

The London Focus group valued the atmosphere to be one of the ‘top tier aspects’ they sought.

Speaker 2, London

“Like there’s a full band playing whatever. You’re like, I’ll go there again, because I know they’ve got a good atmosphere.”

Again, highlighting the differences from major events to a grassroots one, and has perhaps highlighted some issues surrounding popular events:

Speaker 3, London

“Like when I go into a major venue like an arena, there is an element and a feeling like cattle. I don’t feel like cattle when I go to a grassroots venue.”

Speaker 3, London

“I think to sum it up in one sentence. Every single time I’ve been to a bigger venue, like a major venue, I felt like an inconvenience. When I go to most grassroots, most, but not all of them, but most of them I feel much more welcomed.”

As discussed, the atmosphere goes hand in hand with the community aspects, as it is often the community at the event that creates an ideal atmosphere.

Supporting Your Local/Venue

Participants expressed motives for wanting to support their local and supporting a particular venue or grassroots venues in general.

Speaker 2, Brighton

“It’s a case of not just supporting musicians, it’s a case of supporting near you.”

Speaker 1, Brighton

“It only lasted a year or so, but it was kind of quite magical while it was there, and I think a lot of us went just because we wanted the venue to continue doing what it was doing. I can’t remember any of the artists I saw.”

Speaker 3, Ipswich

“It’s also helping the smaller venues survive as well because they’re the ones who need the support.”

Speaker 2, Brighton

“And I was going to say about supporting the actual promoters so as well as supporting the venue and the artist supporting the promoters. And you know, these sort of grassroots venues that people put and their shows on there, do it because they love music. And very often they will lose money and it’s about really supporting them as well.”

An excellent point was made that the particularly small grassroots venues do not tend to make much money but put on events for the love of music, which is included in the Grassroots venue definition (see literature review).

Motives were also expressed to support up and coming musicians:

Speaker 2, Brighton

“Where the support I’m really interested in, and that’s what’s made me go rather than the attraction of the main act.”

Some participants went solely to support their friends:

Speaker 4, Ipswich

“For other people, you might be going with somebody to support them because there’s somebody there, we travelled to London I think to KoKo’s in Camden. I just support one of our friends who wanted to see Trombone Shorty so three of us rocked up because one person wanted to go. I never heard of him, so that might be a factor for other people.”

Speaker 3, London

“All I’m going for is the bands that I know I’ve got friends in.”

Interestingly, a member from the London focus group expressed that they would not care if a grassroots venue closed down, showing that everyone does not share this motivation.

Speaker 3, London

“I’ve never once gone to The Boileroom or any grassroots venue and said, I’m just glad to be here because I don’t want this place to close down. I am a full on advocate for capitalism. The supply and demand. They **** themselves up through whatever means, even if it’s unfair, that’s the way to go.”

This comment is slightly detrimental to the smaller scaled grassroots venues that put on events, not for the money but the love of music and not to profit. Though another question does arise, will small grassroots venues survive in the future if they do not bring in any money? Hopefully, this paper can help organisers be more business- minded in their marketing and yet maintain the essence of their creative and artistic activities.

Good Reputation

This theme was important for the London focus group but not for the other groups.

Speaker 3, London

“I think number one above everything else is the reputation of a venue. If it, if it is known and the people around me and the count of people there, is telling me that they’ve had countless great experiences after great experiences after great gig after great gig after great night out at that venue. I’m much more inclined to go in yeah, and if there’s a night or a theme or something like that incentivises me, then even better.”

Reputation was a big theme in the London focus group, and if consumers hear of other consumers having a great experience via word of mouth, they are much more likely to attend the next event.

Speaker 1, London

“If it had a sort of a reputation for being quite an enjoyable night, having a good vibe, like a good crowd of people. That kind of thing. That would be quite a strong incentive, even if I didn’t know who was playing. You know, if there’s like a good crowd, a good scene, it’s got a reputation there like being a fun night if they’re having fun people there, then yeah.”

In this quote, the themes of Community and Atmosphere also add to the event/venue’s reputation.

Cheap Night

This last motivational theme came up in all three focus groups and indicates that it is a factor in the consumer’s decision-making process of whether to attend.

Speaker 1, London

“Yeah, I mean the festival costs £250, whereas a grassroots venue costs £5.”

Speaker 1, Ipswich

“It’s not such an expensive night out.”

Speaker 1, Brighton

“It only cost a couple of quid.”

Does this theme exert a push on an individual to attend, or is it merely a preference? The following section will see that the pricing of these events can certainly be a deterrent.

5.3 Preventatives to Attend

This research will now explore each preventative theme in detail:

Bad Reputation

Reputation was a big motivational theme for the London Focus Group; however, they quickly realised that “reputation can be a prevention” (Speaker 4, London).

The participants reminisced of stories from their student days about specific venues having a terrible reputation and how it was preventative to their attendance to such places. Whilst these venues may get a bad reputation from their own actions, they also get a bad reputation from audiences’ actions, e.g. ‘the spiking of drinks’ (Speaker 1, London).

Interestingly, reputation is a more significant factor for some than others and can be a strong deterrent if another person in the group only goes to places with a good reputation.

Speaker 4, London

“Yeah, I’m big on reputation, however, I’m still gonna go. But if it’s just me and the missus, yeah, **** me am I going to avoid it.”

To limit the effect of this preventative theme, event organisers must have quality measures to ensure that the consumers’ experience is always positive after attending an event; this should lead to the event having a good reputation by consistently providing a great experience. Market research could help find out if a specific venue/event has a bad reputation.

Fear of the Unknown/Intimacy

The ‘Fear of the Unknown’ was an In vivo code found in the transcripts and describes the theme perfectly. It is typical from a psychological perspective that people are generally afraid of things they have not experienced before. Intimacy, the unique selling point of Grassroots venues, was also found to be a barrier.

Speaker 3, Brighton

“The fear of the unknown! That was on my mind, if people have never been to a particular venue before. The idea of Grassroots venues for some perhaps… well what does that even mean? And even fear of intimacy as well. If you are up close, I guess it’s the same as being on the front row of a comedy act and being brought onto the show or humiliated as part of that. I guess it’s a part of that. I’ve been to shows, I have a friend who lives in New York, and I tend to want to go out. So I go to venues such as Arlene’s Grocery, and in the lower East side, so some really very small venues. You walk in there and everybody looks round, and it might be in the middle of a solo acoustic performance, and all of a sudden the spotlights on you! That happened to me the first time I went there and there was this sense of, should I go there again? I’m not quite sure on that place. I forced myself to go, and it turned out to be the best part of that holiday in my life! It was fantastic! Being in a small venue with such variety of artists. But yeah fear, I guess might be a barrier, a fear of the unknown and a fear of the intimacy.”

Speaker 2, Brighton

“I think a lot of people are scared to try something new. So unless the artist is really well known, or has been played a lot on the radio, they won’t take a chance on them, so they won’t go to the Grassroots venues.”

Is there anything organisers can do to prepare or inform consumers of the sort of experience they might expect so that the ‘unknown’ barrier is broken down?

Expensive

This theme was only mentioned in the London Focus Group and could be because money is more of an issue for students than it is for older demographics who have already progressed in their careers and have an income.

Speaker 3, London

“How many times have we not gone to (a particular venue in Guildford) due to the pricing?”

Speaker 2, London

“I’m always a bit peeved when I have to pay an entry fee.”

If a venue is holding an event aimed at younger demographics, they need to have prices that reflect the audience they are trying to attract.

Limited Facilities

This theme only appeared in the Ipswich focus group, where participants who generally struggle to stand for long periods expressed that venues should accommodate the needs of these people more by providing seating.

Speaker 1, Ipswich

“I think there is more that they could do to encapsulate a wider audience by having some seating of some description.”

Speaker 4, Ipswich

“I don’t stand anymore. Somebody 30 years younger might like to stand all the while and won’t be bothered.”

The participants also expressed that they would make a special effort in standing if it were someone they particularly wanted to see, e.g. ‘Roachford‘ (Speaker 4, Ipswich). Thus suggesting that these people would perhaps go to more grassroots music events if there were seating. If Grassroots event managers consider this, they may draw in more consumers.

No Good Drinks

This preventative theme is interesting as if the motivational theme of “Good Drinks” is not provided, the participants would not go to the event.

Speaker 4, London

“You know, do they have good pints? If not, I don’t (go).”

Speaker 3, Ipswich

“It would certainly put me off going if there wasn’t any sort of drink or that sort of possibilities there.”

Events must ensure a good selection of drinks, and if consumers are aware of this (through marketing material), they may be motivated to attend.

Bad Location

Location was important for the London Focus Group.

Speaker 3, London

“The other big thing about the importance of whether I do or don’t attend a grassroots venue, The (undisclosed venue) represented perfectly again in the context of Guilford, is location. I’m not gonna trek my **** half an hour, 45 minutes away from spoons, which is the natural progression? Let’s be honest. Basically, Grassroots events need to happen in close proximity to Wetherspoons.”

If an event is challenging to get to (poor transport links), in a part of a city which has a bad reputation or is a long distance to the city centre where many people may go afterwards to continue their night, it can be a substantial preventative to attendance. Many Grassroots events that occur in a fixed physical location can not do much to help this situation other than providing travel information to reassure participants or choosing a suitable location in the first place when setting up the venue.

Wrong Expectations

The last preventive theme was Wrong Expectations. This theme suggested that some people would not go to a grassroots music event because they had different expectations of what the event would entail. This passage in the Brighton Focus Group was insightful:

Speaker 2, Brighton

“I think a lot of people are scared to try something new. So unless the artist is really well known, or has been played a lot on the radio, they won’t take a chance on them, so they won’t go to the Grassroots venues.”

Speaker 1, Brighton

“Then if they do go and see them, they expect it to sound like the record on the radio. I remember seeing Neil young, and loads of people in the audience felt pissed off as he didn’t play his big hits. He played whatever he wanted to play for two hours. So again, that thing where people aren’t willing to take a chance. I think if people go to the O2 Arena they’re expecting to see slick costume changes, massive professional sound systems. There’s no randomness, nothing left to chance, and everything’s well-choreographed and probably made to sound like it does on the recorded version. A bit boring I think.”

Major events’ high stage production is so widely different from a grassroots performance where music is the primary offering, rather than audio/visual at a larger event with choreographed dance routines, visual stage effects, lighting rigs and pyrotechnics. Perhaps grassroots venues could look into investing more stage equipment to enhance its visual aspect and attract more of these people, but this could undermine the authentic music experience theme that is so strongly desired, as well as being expensive to implement, which will be out of reach for many of the smaller- scaled grassroots events.

6. Discussion of Research Findings

When looking at the data, it is important not to analyse this quantitatively, as in this research the value of what a particular group said is significant, even if other groups did not mention the same theme. It is also essential to recognise that the data will not be entirely representative in a group, and that individuals’ preferences will be different from the groups’ collective preferences. However, through the numbers, we can see how many times a code came up for a particular theme and see that some themes were more important for some groups than others. This research will now understand the nature of the focus group sessions and explore each theme in-depth.

6.1 Discussion of Focus Groups

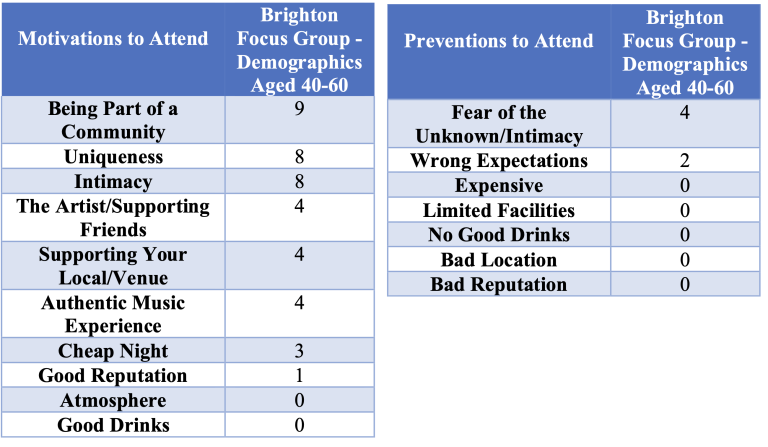

Table 5: Brighton Focus Group – Results

The results of this focus group indicated that Being Part of a Community was the highest motivational factor, followed closely by Uniqueness and Intimacy.

This focus group was held with working professionals during a break from their work, and this could attribute to why ‘Good Drinks’ was undiscussed as the colleagues may not have wanted to disclose this information whilst at work.

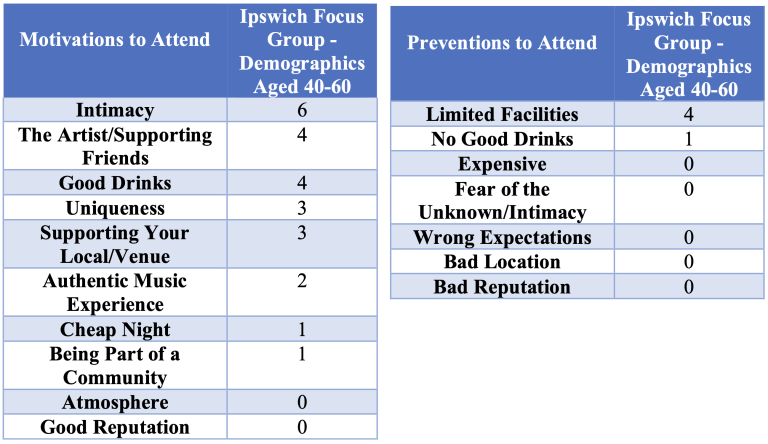

Table 6: Ipswich Focus Group – Results

This research focus group was implemented after work with a group of friends, and their primary motivations were Intimacy, The Artist/Supporting Friends and Good Drinks. Limited facilities, especially ‘lack of seating’, was a considerable insight into the preventions from attending an event for this demographic. The session was the shortest duration out of the focus groups (00:28:44), which is perhaps why the themes’ data came up shorter than the other groups and why Reputation or Atmosphere was undiscussed.

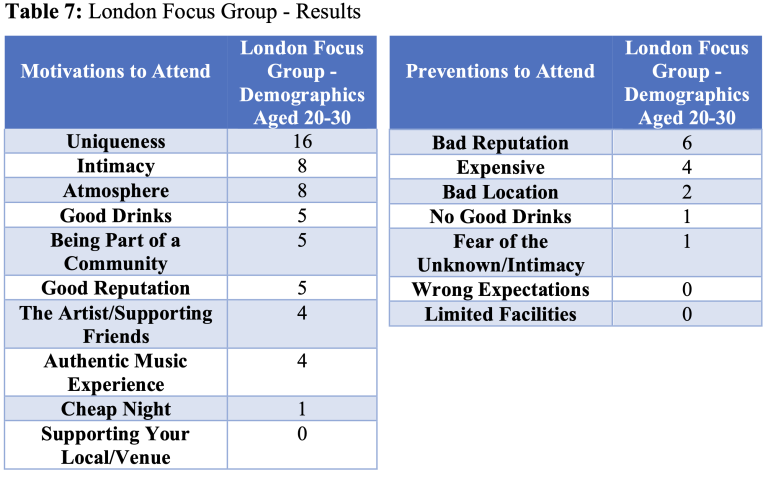

Table 7: London Focus Group – Results

This research was held in the late evening in a relaxed environment and found that the most significant motives were Uniqueness, Intimacy and Atmosphere. Being Part of a Community was a big focus and was attributed to the Atmosphere factor. As recent students, Good Drinks was a significant factor, and Bad Reputation, Expensive and Bad Location being high preventions to attend. Interestingly, this group expressed that they did not care about supporting the venue. Another interesting finding was that Atmosphere was one of the most critical aspects; however, this was undiscussed in the other groups.

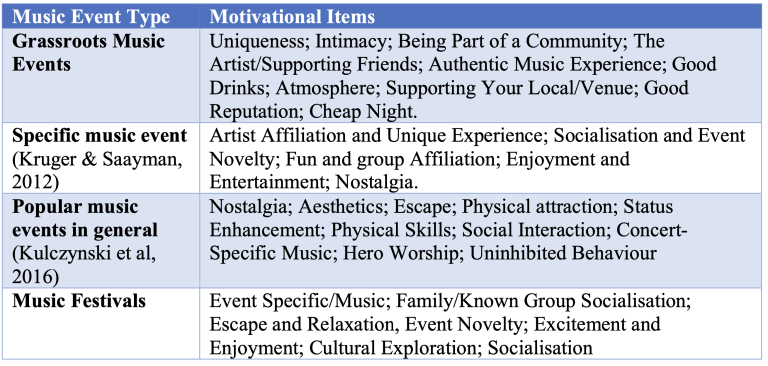

6.2 Music Event Motivations Comparison

This research has added to the existing literature on motivations for attending music events by researching another music event type (grassroots). The data surrounding music festivals are much more credible due to the sheer amount of research completed in this field, and more research is needed in popular music events and grassroots events to give more accurate data. Nevertheless, some comparisons are visible. In all of the research, there were motives in attending concerning things other than music, the primary offering (see table 8).

Table 8: Music Event Type Motivational Comparison

The event size plays a significant role and adds motivational strengths to each event type. For instance, the small size of grassroots events adds Uniqueness, Intimacy, an Authentic Music Experience and a concentrated Atmosphere. In contrast, the larger events such as a festival have the space to offer more incentives other than the music by compartmentalising a field and planning spaces for specific experiences such as Escape and Relaxation, Socialisation, Cultural Exploration and a heightened Excitement by creating highly visual and high production value stages. It could be said that as festivals offer more incentives other than music, that they attract more ‘recreational attendees’ than ‘avid fans,’ though more research should be conducted to clarify this.

7. Conclusion

Overall, this research has better understood consumers’ motivations and preventions to attending a grassroots event. Through undertaking focus groups with participants based in three cities around the UK (Brighton, Ipswich and London), this research has concluded that there were ten motivations to why someone would attend a grassroots venue, these were: Uniqueness; Intimacy; Being Part of a Community; The Artist/Supporting Friends; Authentic Music Experience; Good Drinks; Atmosphere; Supporting Your Local/Venue; Good Reputation; Cheap Night. These motivations may help event organisers bring in more business by considering these motivational themes in their event planning and fulfilling consumer preferences. This research found out in the literature review and acknowledges that many of the small-scale Grassroots events are not for profit and merely run events for the sheer passion of music. However, the motivational themes found can ultimately lead to a better experience for all parties involved, be it the community, the audience, musicians or event organisers, where a unique and intimate setting within a community can celebrate up and coming music authentically.

This research also concluded that seven preventative themes were surrounding attending a Grassroots event: Bad Reputation; Fear of the Unknown/Intimacy; Expensive; Limited Facilities; No Good Drinks; Bad Location; Wrong Expectations. Event organisers can limit as many of these preventative themes as possible by tending to each issue separately. Possible measures were suggested in the discussion of findings section, suggesting that: to combat Bad Reputation, events managers could conduct market research to understand their reputation and employ quality assurance practices to their events and gain reputation; to combat Fear of the Unknown/Intimacy, find ways of informing and preparing audiences the type of experience they may encounter (possibly highlighting the positive themes); to combat Expensive, have prices that reflect their target audience; to combat Limited Facilities, event organisers could seek to invest in their facilities, such as providing seating to attract members of the public who can not stand for long periods; to combat No Good Drinks, ensure that there is an excellent selection of drinks; to combat Bad Location, choose another place to run the events or inform/suggest ways to get to the events; to combat Wrong Expectations, event managers could inform consumers more about the type of experience they can expect, or weigh up their options in investing in more stage equipment or visual effects, though, this could have a negative effect on the motivational theme Authentic Music Experience.

Overall, this research has contributed and hopefully filled a gap in the music event literature by providing insights into consumer motives behind attending Grassroots venues, of which it was discovered that there was a lack of research in this particular area. The motivational comparison across music event types found that each event types primary consumer motivations were because of attributes brought out by the event size.

8. Recommendations

This research has identified a gap in the literature and has attempted to fill that gap. It is recommended that more research is conducted in this area to validate further the data and conclusions drawn. The literature also identified that one could better understand consumers by seeing if they fit in a particular group. It is recommended that future research conducts a questionnaire or survey on Grassroots event attendees asking socio-demographic questions, and at the same time possibly including a Likert scale with the motives found in this research. Cluster analysis could be implemented, and this could generate insights to see if any consumer preferences fit a particular group, e.g. consumers at a certain age, in a specific geolocation, a level of education or salary. This research would provide even greater insights into consumer motives behind attending music events.

More research could also be conducted in the popular music event type category as research is sparse in this area. More research could also be conducted exploring consumer preventions to attending; much of previous research focussed heavily on the motivations.

Event managers who run music events should take the conclusions of this paper and see if there is anything they can do to better their events by fulfilling the motivations found and solving all of the preventative factors that could be associated with their event. This paper looked at grassroots events as a whole, and the data here may not be helpful for every event. Events are highly unique, and it is recommended that event managers conduct their own research into their own specific unique events to get the most accurate and valuable data to fulfil their needs. It is also recommended that event managers follow the PMBOK or EMBOK advice, whereby the ‘closure’ phrase is properly initiated and a ‘feedback & review’ is completed. The closure of the event will indicate what went well and what needs improving for the particular event and generate highly relevant information “that will facilitate the effective transfer of knowledge to the next event project” (EMBOK, 2004).

9. List of References

Anderton, C. (2008), “Commercializing the Carnivalesque: The V Festival and

Image/Risk Management”, Event management, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 39-51.

Anderton, C. (2020), “From Woodstock to Glastonbury to the Isle of Wight: The Role of Festival Films in the Construction of the Countercultural Carnivalesque”, Popular music and society, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 201-215.

Bakhtin, M. (1984), Rabelais and his world, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Ind.

Blake, A. (1997), The land without music: music, culture and society in twentieth- century Britain, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Blešić, I., Pivac, T., Stamenković, I. & Besermenji, S. (2014), “Investigation of visitor motivation of the EXIT music festival (the Republic of Serbia)”, Journal of Tourism – Studies and Research in Tourism, vol. 18, pp. 8-15.

Bowen, H.E. & Daniels, M.J. (2005), “Does the music matter? Motivations for attending a music festival”, Event Management, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 155-164.

Brown, S.C. & Knox, D. (2017), “Why go to pop concerts? The motivations behind live music attendance”, Musicae scientiae, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 233-249.

Brown, A.E. & Sharpley, R. (2019), “Understanding Festival-Goers and Their Experience at UK Music Festivals”, Event management, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 699-720.

BVEP. (2020), “The UK Events Report”. [Online]

https://www.excel.london/uploads/uk-events- report-2020—the-full-report.pdf

[Accessed 27th April 2021]

Clarke, M. (1982), The politics of pop festivals. London: Junction Books Ltd.

Cluley, R. (2009), “Chained to the grassroots: the music industries and DCMS”, Cultural Trends, vol. 18, pp. 213-225.

Crompton, J.L. & McKay, S.L. (1997), “Motives of visitors attending festival events”, Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 425-439.

Dodgson, J. E. (2019) “Reflexivity in Qualitative Research”, Journal of Human Lactation, 35(2), pp. 220–222.

EMBOK, (2004), “Updated EMBOK Structure as a Risk Management Framework for Events”. [Online] https://www.embok.org/juliasilvers/embok/EMBOK_structure_update.html#Phases [Accessed 27th September 2021]

Faulkner, B., Fredline, E., Larson, M. & Tomljenovic, R. (1999), “A marketing analysis of Sweden’s Storsjӧyran Musical Festival”, Tourism Analysis, vol. 4, no. 3/4, pp. 157-171.

Gelder, G. & Robinson, P. (2009), “A Critical Comparative Study of Visitor Motivations for Attending Music Festivals: A Case Study of Glastonbury and V Festival”, Event Management, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 181-196.

Getz, D. (2005), Event management & event tourism, 2nd edn, Cognizant Communication, New York.

Getz, D. (2012), Event studies: theory, research and policy for planned events, 2nd edn, Routledge, Abingdon.

Hayton, J.C., Allen, D.G. & Scarpello, V. (2004), “Factor Retention Decisions in Exploratory Factor Analysis: a Tutorial on Parallel Analysis”, Organizational research methods, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 191-205.

Hetherington, K. (1992), Stonehenge and its festival: Spaces of consumption, London: Routledge.

Hetherington, K. (2000), New age travellers: vanloads of uproarious humanity, London: Cassell.

Hewison, R. (1987), Too much: art and society in the Sixties 1960-75, Oxford University Press, New York.

Hodak, D.F., Belošević, G. & Vlahov, A. (2020), “Towards better understanding electronic music festivals motivation”, Zagreb international review of economics & business, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 141-154.

Homan, S. (2010), “Government as anything: live music and law and order in Melbourne”, Perfect Beat: the Pacific journal of research into contemporary music and popular culture, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 103-118.

Jones, P. (2002), “Anarchy in the UK: ’70s British Punk as Bakhtinian Carnival”, Studies in popular culture, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 25-36.

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). “Likert Scale: Explored and Explained.” Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 396-403.

Kim, H. D., La Vetter, D., & Lee, J. H. (2006), “The influence of service quality factors on customer satisfaction and repurchase intention in the Korean Professional

Formica, S. & Uysal, M. (1996), “A market segmentation of festival visitors: Umbria Jazz Festival in Italy”, Festival Management and Event Tourism, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 175-182.

Basketball League”, International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 39–58.

Kinnunen, M., Luonila, M. & Honkanen, A. (2019), “Segmentation of music festival attendees”, Scandinavian journal of hospitality and tourism, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 278- 299.

Kotarba, J. A., & Vannini, P. (2009). Understanding society through popular music. New York: Routledge.

Kruger, M. & Saayman, M. (2012), “Listen to Your Heart: Motives for Attending Roxette Live”, Journal of convention & event tourism, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 181-202.

Kruger, M. & Saayman, M. (2019), “’All that jazz’: the relationship between music festival visitors’ motives and behavioural intentions”, Current issues in tourism, vol. 22, no. 19, pp. 2399-2414.

Kulczynski, A., Baxter, S. & Young, T. (2016), “Measuring Motivations for Popular Music Concert Attendance”, Event management, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 239-254.

Liu, Y. & Chen, C. (2007), “The effects of festivals and special events on city image design”, Frontiers of architecture and civil engineering in China, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 255-259.

Li, Y. & Wood, E.H. (2016), “Music festival motivation in China: free the mind”, Leisure studies, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 332-351.

MacDonald, R.R. (2002), Musical Identities, Oxford University Press.

Martell, L. (2017), The sociology of globalization, Cambridge: Polity.

McKay, G. (2000), Glastonbury: A very English fair. London: Victor Gollancz.

McMorland, L. & Mactaggart, D. (2007), “Traditional Scottish music events: native Scots attendance motivations”, Event Management, vol. 11, no. 1/2, pp. 57-69.

Moutinho, L. (1987), “Consumer Behaviour in Tourism”, European journal of marketing, vol. 21, no. 10, pp. 5-44.

Muhs, C., Osinaike, A. & Thomas, L. (2020), “Rave and hardstyle festival attendance motivations: a case study of Defqon.1 weekend festival”, International journal of event and festival management, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 161-180.

Music Venues Trust. (2021), “Grassroots Music & Arts Space (GMAPs) Definition”. [Online] https://musicvenuetrust.com/resources/grassroots-music-arts-space-gmas- definition/ [Accessed 18th September 2021]

Music Venues Trust. (2021), “Grassroots Music Pub (GMPs) Definition”. [Online] https://musicvenuetrust.com/resources/grassroots-music-pub-gmps-definition/ [Accessed 18th September 2021]

Music Venues Trust. (2021), “Grassroots Music Venue (GMVs) Definition”. [Online] https://musicvenuetrust.com/resources/grassroots-music-venue-gmvs-definition/ [Accessed 18th September 2021]

Nicholson, R.E. & Pearce, D.G. (2001), “Why do people attend events: a comparative analysis of visitor motivations at four south island events”, Journal of Travel Research, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 449-460.

Nowell, L.S., Norris, J.M., White, D.E. & Moules, N.J. (2017), “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria”, International journal of qualitative methods, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1-13.

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Dickinson, W.B., Leech, N.L. & Zoran, A.G. 2009, “A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research”, International journal of qualitative methods, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1-21.

Özdemir Bayrak, G. (2011), “Festival motivators and consequences: a case of Efes Pilsen Blues Festival, Turkey”, Anatolia: an international journal of tourism and hospitality research, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 378-389.

Paleo, I.O. & Wijnberg, N.M. (2006), “Classification of Popular Music Festivals: A Typology of Festivals and an Inquiry into Their Role in the Construction of Music Genres”, International journal of arts management, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 50-61.

Parliament UK. (2019), “Challenges Facing Music Venues” [Online] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/733/73307.html [Accessed 17th September 2021]

Pegg, S. & Patterson, I. (2010), “Rethinking music festivals as a staged event: gaining insights from understanding visitor motivations and the experiences they seek”, Journal of Convention and Event Tourism, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 85-99.

Perron-Brault, A., de Grandpré, F., Legoux, R. & Dantas, D.C. (2020), “Popular music festivals: An examination of the relationship between festival programs and attendee motivations”, Tourism management perspectives, vol. 34, pp. 100670.

Pilcher, D.R. & Eade, N. (2016), “Understanding the audience: Purbeck Folk Festival”, International journal of event and festival management, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 21-49.

Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2019), Research methods for business students, Eighth edn, Pearson, Harlow.

Solomon, M.R., Askegaard, S., Hogg, M.K. & Bamossy, G.J. (2019), Consumer behaviour: a European perspective, Seventh edn, Pearson, Harlow, England.

Stallybrass, P. & White, A. (1986), The politics and poetics of transgression, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Thrane, C. (2002), “Jazz Festival Visitors and Their Expenditures: Linking Spending Patterns to Musical Interest”, Journal of travel research, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 281-286.

UKMusic. (2019), “Music By Numbers 2019”, [Online] < https://www.ukmusic.org/wp- content/uploads/2020/08/Music_By_Numbers_2019_Report.pdf > [Accessed 27th April 2021]

Van der Hoeven, A. & Hitters, E. (2019), “The social and cultural values of live music: Sustaining urban live music ecologies”, Cities, vol. 90, pp. 263-271.

Vinnicombe, T. & Sou, P.U.J. (2017), “Socialization or genre appreciation: the motives of music festival participants”, International Journal of Event and Festival Management, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 274-291.

Worthington, A. (2004). Stonehenge: Celebration and subversion, Loughborough: Alternative Albion.

10. Appendices

Moderator: